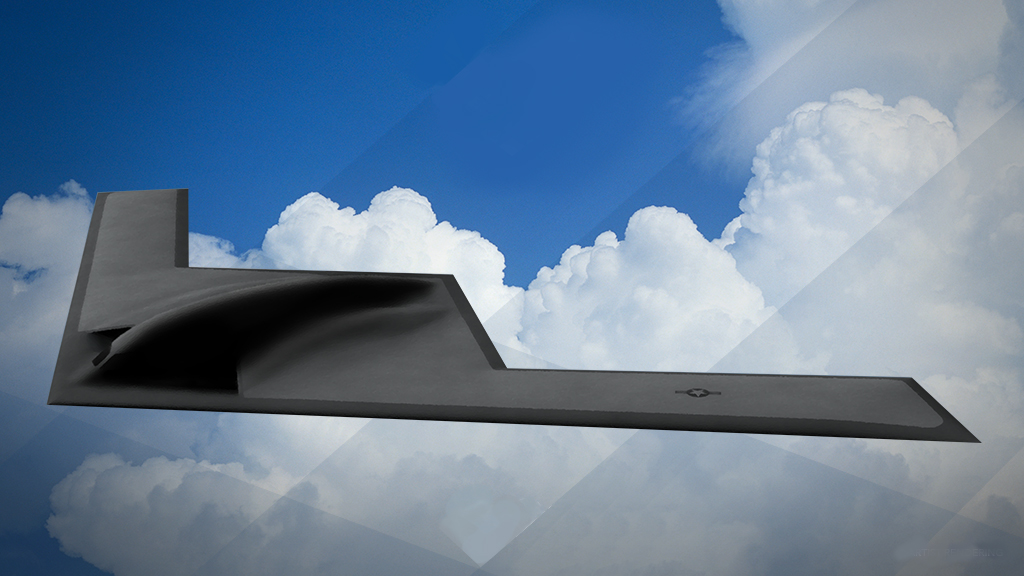

Air Force illustration of the B-21 Raider long-range strike bomber.

Northrop Grumman’s willingness to spend more of its own money on design, development, and initial production gave it the advantage in the Air Force’s B-21 bomber contract, according to documents released by the Government Accountability Office late Tuesday.

The heavily-redacted findings of the GAO in assessing Boeing’s protest of the award to Northrop Grumman—resolved in Northrop’s favor early this year—show the award was based solely on who could offer the “lowest-price technically acceptable best-value approach … with no credit for exceeding the requirements.”

There was a formula for winning by offering more capability at a slightly higher price, but apparently this did not come into play. The GAO said Northrop’s bid was “substantially” lower than the Boeing-Lockheed Martin team’s, due to “Northrop’s corporate investment decisions” to eat more of the development cost, along with Northrop’s somewhat lower labor rates and predicted labor rates.

The unnamed source selection authority told the GAO both companies were “aggressive” in their pricing, to the degree that neither could prove that it could do the work for what the Air Force, through independent cost estimates, thought the work was worth.

In their zeal to hold costs down, both competitors initially offered bare-bones designs, which the Air Force rejected as “unacceptable” in their capabilities. Through a dozen subsequent meetings with both competitors, both designs were refined and ultimately accepted.

The Air Force apparently recognized that going with the rock-bottom bid posed some risk to schedule, but thought it was within acceptable limits, given the “substantial cost/price advantage” Northrop offered.

The GAO’s report shows that the bomber program started in 2004, and Boeing, Lockheed Martin, and Northrop were the competitors. By 2007, it became the Next Generation Bomber, by which time Lockheed had joined Boeing as a partner. When the NGB was cancelled in 2009, all three companies got contracts to continue working on “risk reduction and cost savings efforts.”

When the program got going again in 2011 as the Long-Range Strike Bomber, the Air Force was focused on producing an aircraft from “mature … integration-read” technologies with low risk.

In a memo explaining its intent, USAF said it meant to “keep requirements stable, manageable, and tradeable to ensure affordability.”

The GAO’s report suggests strongly that subscale concepts or prototypes were “demonstrated” and both designs passed an Air Force preliminary design review.

Boeing protested the award to Northrop because it felt the risk associated with Northrop’s super-low bid wasn’t adequately accounted for in the evaluation process, and Northrop should have had its likely higher costs counted against it. Boeing also complained that its own bid didn’t get credit for expected lower costs from production innovations under the so-called “Black Diamond” program. The GAO rejected those arguments, saying Northrop’s costs were reasonably estimated and Boeing couldn’t adequately justify its own anticipated lower costs.

Boeing is likely applying “lessons learned” from the bomber in its pursuit of the T-X trainer contract. Company officials have said their clean-sheet design T-X, revealed in September, hews strictly to the requirements as stated, with almost no additional capability added that could increase costs beyond what the company thinks the Air Force is willing to pay.