The 33rd Network Warfare Squadron relies on a $543 million weapon system called Air Force Cyber Defense to help it guard the Air Force's network from intrusions. Photos/Illustrations: Jessica Turner/USAF; SSgt. Alexandre Montes.

Every single day, the cyber warriors at the 33rd Network Warfare Squadron come face to face—keystroke to keystroke—with hundreds of attacks against the service’s main and massive network.

To help them accomplish the squadron’s mission to defend the full Air Force Network (AFNET)—which the service uses for daily business, like emails and file sharing—it operates and relies on a special sidekick, the Air Force Cyberspace Defense (ACD) weapon system. The $543 million, custom-built suite of devices and programs is deployed throughout the AFNET ecosystem, always watching it, ever reactive to suspicious activity it recognizes.

It’s “fairly defined terrain,” said Lt. Col. Samuel Snoddy, commander of the 33rd NWS, which operates out of JBSA-Lackland, Texas. By that, he means the squadron’s 306 cyber warriors—comprising military, civilian, and contract personnel—know they’re defending between 600,000 and 700,000 cyber “endpoints” 24 hours a day, seven days a week, 365 days a year. Simply put, endpoints are keyboards or other devices allowing interaction with USAF’s internal networks—whether by friend or foe. Out of USAF’s seven cyber weapon systems and the teams operating them,“We have the largest terrain,” Snoddy said, adding that all the systems complement each other.

Traffic to and from AFNET’s endpoints spills into creeks of data flow, subsequently branching into rivers and eventually into any one of the 16 existing gateways currently governing all AFNET traffic. ,

“The gateways are very complex architecture that support massive amounts of traffic and data flowing through them,” Snoddy told Air Force Magazine. “[There are] probably hundreds of devices and programs that make up each one of these gateways across the Air Force.”

The ACD weapon system is able to spot abnormalities because it knows “what good traffic looks like,” Snoddy said.

“It’s the border wall,” he summarized. “If we see something we don’t like, we stop it at the gate.”

To this end, when ACD determines an activity fits certain conditions, it categorizes it in one of nine escalating levels. When that happens, a response protocol triggers. Depending on the category, ACD may resolve the issue itself or it may alert a cyber warrior, compelling that person to initiate other protocols to get a better understanding of what’s happened.

The top category is “the absolute worst-case scenario from a defensive operations perspective,” explained Capt. Anthony Rodriguez, the 33rd NWS’s director of operations. Category 1 means an adversary has gained “privileged [administrative/authoritative] control over an endpoint,” he said, adding such an adversary could potentially exfiltrate data, further explore the network, or “even use it as a launchpad for attacks against the critical mission systems utilizing our networks.” The last Category 9 describes a “benign or non-malicious” event.

The 33rd has to be concise in eliminating threats and lax enough to allow the flow of normal data and not “hinder the mission.” While Snoddy said the squadron opens more than 1,000 investigations each year, on average (each one representing an activity requiring human intervention of one kind or another), defining success in defending AFNET is tricky.

“It’s something I’m trying to refine and tweak,” Snoddy said. “It’s very dynamic. It’s hard to narrow down success rate because you don’t know what you don’t know.”

In the last 12 months, Rodriguez told Air Force Magazine, the 33rd has opened up 1,500 investigations. One major challenge facing the squadron is Category 9s coming from “our own people,” Snoddy said.

Airmen may make mistakes while using an AFNET endpoint, or do things they’re not supposed to be doing. Training is one way to fix this issue. Automated network protections is another method toward healthier cyber hygiene, stopping these non-issues in their tracks.

Constantly building the tools the 33rd needs to face newer and tougher threats is the squadron’s hardest challenge.

“Everyday, we’re being attacked. Hundreds—if not thousands—of times a day, there are bad people trying to get into our systems and do bad things,” Snoddy said. “It’s trying to keep up with that and it’s staying ahead of that.”

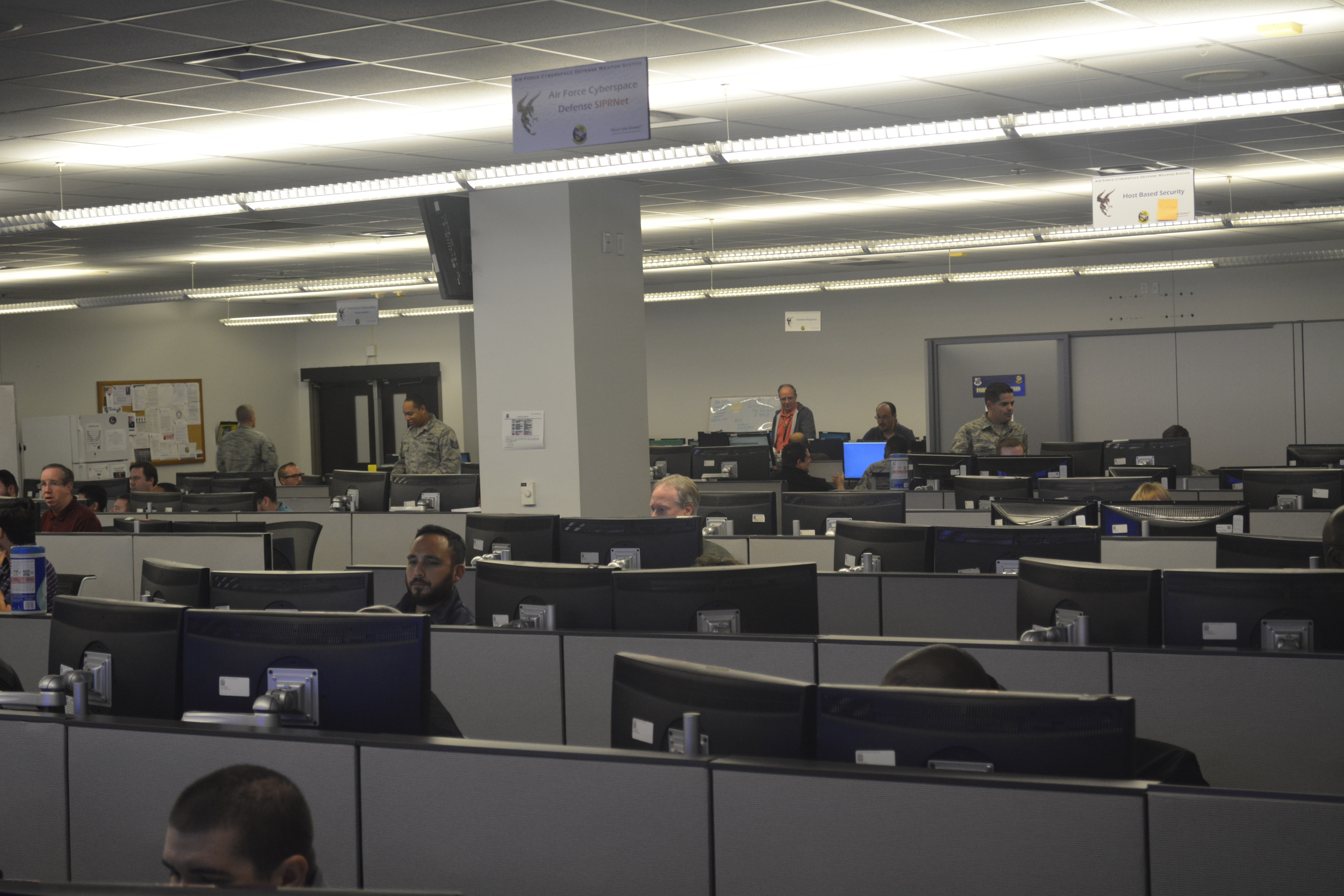

On the 33rd Network Warfare Squadron’s operations floor, cyber warriors face threats to the Air Force’s main network, attending to them every hour of every day. Photo courtesy of 33NWS.

In this regard, the 33rd NWS and its ACD aren’t alone. When cyber warriors encounter a tool or threat in the cyber wild and determine its capability is beneficial either for their own use or for examination, the need is urgent, the requirement potentially immediate.

“We do find it a challenge to have the right set of tools that we need to defend a network and I know there are a lot of things in the works to help that cycle improve,” Snoddy said, adding there are also “a lot of organizations out there” rising to the occasion.

One such helping hand comes from the 90th Cyber Operations Squadron’s cyber operators, who “help get the mission done,” focusing on developing rapid capabilities.

“They’re very talented,” Rodriguez said about the 90th COS’s cyber warriors. “They help us with some of those homegrown needs, on a quick turn.”

In another example, the 33rd found industry partner Tanium’s enterprise remediation tools—”typically used for patching and network monitoring,” Snoddy explained—can also be used for cyber defense. The partnership between Tanium and 24th Air Force—where both the 33rd NWS and 90th COS are housed— resulted in a system dubbed Automated Remediation and Asset Discovery (ARAD), an effort the Department of Defense recognized in December 2016’s cyber excellence awards.

“The team drove an unprecedented eight-month acquisition schedule to deliver tools that enable operators to identify and fix network vulnerabilities in seconds instead of weeks and the ability to detect, track, target, engage, and mitigate adversarial activities in near real time,” DOD’s release about the awards read. “This solution can be leveraged across the federal enterprise.”

On May 23, 2017, 24th Air Force Commander Maj. Gen. Christopher P. Weggeman mentioned ARAD when he testified to the Senate Armed Services Committee’s Subcommittee on Cybersecurity.

“The demonstrated potential of ARAD is truly revolutionary,” he said. “… and we are diligently experimenting, evolving, and developing operational concepts and applications to close key mission capability gaps in close partnership with the Tanium experts.”

On top of in-house and industry partner cooperation of this sort, threats seen outside AFNET are reported to the 33rd NWS, preempting similar attacks on its terrain. Cyber operators will add a technical description of such threats into ACD, adding to its repertoire. Every such addition is called a signature. With each new signature, ACD gets smarter and faster. With the frequency of cyber threats increasing, Snoddy said cyber warriors are adding signatures into ACD “daily.”

How many signatures does it hold today? After a beat, Snoddy said, “I’ll just leave it at: a lot.”

Automation is key in making ACD the beast that it is, but in this battlefield, automation often requires adjustments to deal with new threats, and today that task falls to human hands.

“We’ve been fortunate to have many innovative airmen who think outside of the box,” Rodriguez said.

Snoddy doubled down on the notion: “There’s no device, there’s no magic tool, there’s nothing out there that ultimately is going to be the end all save all,” he said. “It’s people who really make it happen.”

To learn more about the people who make up USAF’s cyber warriors, read January 2018’s cover story, Cyber Warriors Fight USAF’s Most Active, and Secret, War.