“We are going to be in desperate need in my command for a significant retrenchment in commitments, for a significant period of time” after the war, he told reporters April 29. This stand-down would be needed “to restore the health of the units, allow them to get back to basic training, get their basic skills upgraded, [and] upgrade all the new people who have come out of the training pipeline during the course of this operation.”

He said, “We have a real problem facing us three, four, five months down the road in the readiness of the stateside units.”

Operation Allied Force had only aggravated a bad situation. On March 22—two days before the war opened—Hawley went before a Congressional committee to discuss readiness. He told lawmakers that ACC had managed to halt a year-long slide in readiness, but ACC preparedness remained “too low.” He expected recent budget increases to pay off in more spare parts and trained technicians. However, he warned, the improvements had yet to appear and were endangered by continued high operational tempo.

In fact, the physical and financial demands of intense optempo, compounded by the air war, increased USAF’s materiel and personnel shortages. These problems could handicap implementation of the Expeditionary Aerospace Force concept, which USAF embraced as a way to relieve the operational crunch on the force.

Hawley delivered these and other warnings not long before his July 1 retirement. There is no doubt he knew that his words would generate discomfort in some quarters. He was one of the first top officers to issue public warnings about eroding combat readiness, and he had no regrets about it. “I don’t think I’ve been an alarmist,” said Hawley. “I think I’ve just been telling it the way it is.”

Stuck at Low Level

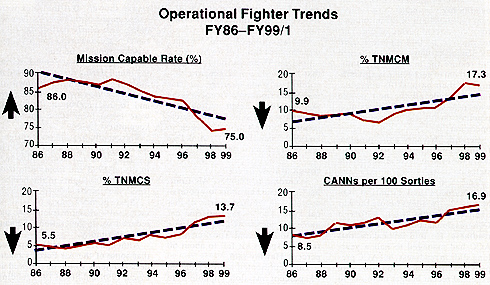

According to Hawley, Air Combat Command had hit its low point in readiness in the first quarter of Fiscal 1998. The average mission capable rate for the ACC fighter force sagged to 74 percent. The typical fill rate in a spares kit fell to about 60 percent, Hawley said.

That represented a drop from an 85 percent mission capable rate among the fighters only two years earlier, according to the official statement Hawley presented to the House Armed Services Committee for his March 22 testimony.

“That’s where we’ve been ever since,” he told reporters.

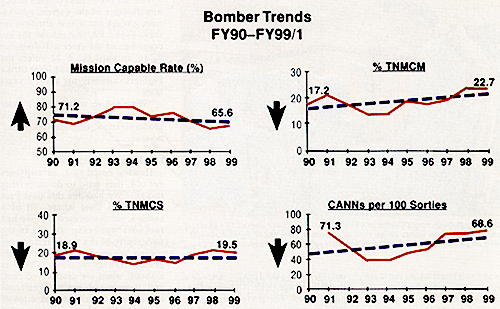

The bomber force had suffered a 10-percentage-point drop, plummeting from about 75 percent in Fiscal 1996 to about 65 percent mission capable rate in early Fiscal 1998, his charts showed. But the rates were worse among certain specific bomber units, with nearly half of the B-1B Lancers at Ellsworth AFB, S.D., not mission capable, he said.

Hawley’s data also showed alarming jumps during that same period in the percentage of aircraft down for maintenance or awaiting spare parts and in the number of times parts were taken from some aircraft to keep others flying.

The cannibalization rate for fighters had gone from about 13 events per 100 sorties in Fiscal 1996 to 16.9 in Fiscal 1998 and from 48 to 68.6 for every 100 flights in the bomber force, the graphs showed.

“Spare parts shortages translate to increased work, more frustration, and reduced sortie generation,” he said in his testimony.

Although Hawley said he expected that some of the Air Force’s readiness problems would be relieved as Fiscal 1998 and Fiscal 1999 funding produced more spare parts, he noted that readiness was affected by other factors that were harder to resolve.

One of these factors was the experience level of personnel within the Air Force generally and his command specifically.

“We have a very low-experience force,” said Hawley, “particularly in Air Combat Command” because the forward deployed units get priority in personnel as well as spare parts.

The lower skill levels among maintenance personnel aggravate the problems caused by the high cannibalization rates because “you run a much higher risk of breaking the part” in the process of moving from one aircraft to another, he explained.

In his Congressional testimony, Hawley explained that lower retention means a shortage of five-level maintenance personnel, the journeymen technicians who “should constitute the bulk of the workforce.”

That means too much of the maintenance work is being done by younger three-level personnel, who require more supervision and take longer to do a job, he said.

And some specialties actually are undermanned because of declining re-enlistment rates and turbulence in training programs caused by the force reductions earlier in the decade, Hawley said.

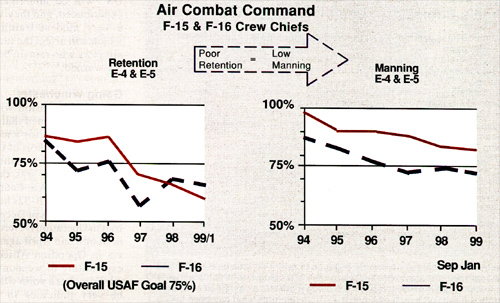

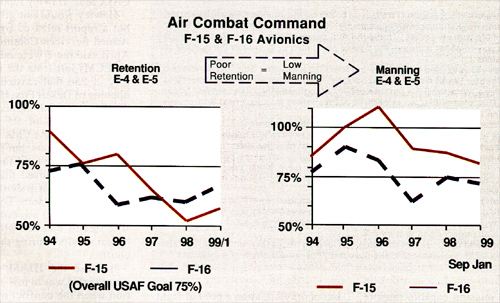

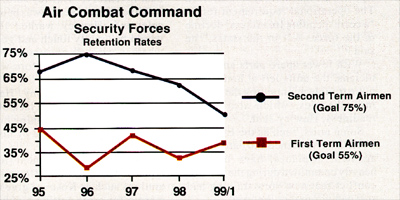

Some of the worst undermanning conditions are found among F-15 and F-16 crew chiefs, F-15 and F-16 avionics technicians, air traffic control specialists, command-and-control systems personnel, and security forces, he said.

Negative Incentive

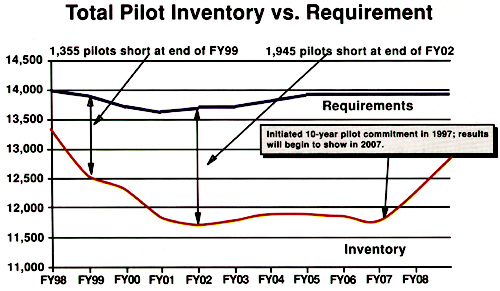

Pilot retention also remains a problem. Although the bonus take rate had increased slightly in early 1999, from about 28 percent to 37 percent, it still was far below Air Force goals and was pointing toward a 2,000-pilot shortage by 2002, Hawley told Congress.

The general called the pilot bonus system a negative incentive for a career in the Air Force because the extra pay peaks at mid-career and then “drops precipitously” in the officer’s later years, when his or her children are reaching college age.

And “many pilots see the bonus as an attempt to bribe them to serve their country,” Hawley said in his House testimony.

“This is simply the wrong way to compensate people for serving the nation,” he said.

The high operational tempo and time away from families are the main reasons pilots give for leaving, not low pay, he said.

Hawley also told the committee that increasing initial pilot training programs is not a solution, because that does not provide the experienced fliers needed to lead flights and sections.

“There are no quick fixes to replacing experienced pilots,” he said.

Another aggravating factor in the readiness decline is the increasing age of the aircraft, Hawley noted.

“We are flying the oldest fleet of airplanes that the Air Force has ever operated,” he said. Hawley noted that the average age of USAF fighters has hit 20 years. The average age of the B-52 is nearly twice that number.

“Old airplanes break in new ways,” said the ACC commander. “When an airplane is new, you’ve got a very predictable pattern of breakage. But the older it gets, the less predictable it gets. They find new parts that begin to wear out, and then you get into lead-time problems because—holy cow—we’ve got a new set of things that are breaking on this 20-year-old airplane, and you don’t have contracts in place.”

The Air Force has no plans to buy new fighters of the current generation, except for a few attrition reserve F-16s. For that reason, the average age of the fleet will continue to go up until the F-22 enters the force in about 2004 and Joint Strike Fighters start arriving several years later.

“We need to sustain [the] older systems while keeping our major modernization programs on track,” he said.

Unpleasant Surprises

Hawley noted that, as airplanes get old, they tend to do surprising things. “We had one this past year in the F-15 fleet where, all of a sudden, we discovered that we had fuel that was being trapped in the underbelly of the airplane and corroding the main spine of the airplane,” Hawley recalled. “That was a shock when we discovered that, and it required some significant corrective action that took a lot of airplanes out of service for a significant period of time. I predict we will have similar surprises as these fleets continue to age. … It takes some of your resilience away.”

Hawley noted that it becomes more difficult every year to keep replacement parts on hand. Accident rates also can go up among older aircraft because of failures in flight, he said. Increased engine failures appear to be a factor in the recent jump in accidents involving F-15s and F-16s, he said.

Said Hawley, “Life gets tougher when you put all this together.”

Then the conflict in the Balkans made things even tougher, Hawley said in his late April session with defense reporters.

NATO’s effort to stop the Serbian ethnic-cleansing drive in Kosovo aggravated the readiness problems of ACC’s US–based units by draining away much of the limited stores of spare parts and many of the best trained personnel, he said.

“We are noticing the strain today,” Hawley said.

And he warned that the deployment of additional aircraft that the NATO commander requested in early May would increase those strains.

Hawley said, “The forward deployed forces [ACC units dispatched to Europe, Asia, and the Persian Gulf] are in pretty good shape, … [with] very good mission capable rates in almost all those systems, but that is because we give them a lot of priority.” He explained that forward units get the most experienced people, full spares kits, and extra aircrews.

As a result, however, “the forces left behind in the United States … are seeing a decline in readiness,” said Hawley. He added, “I expect that will become more aggravated the longer this operation continues, because we are obviously obligated to fully support those forces that are actively engaged on a day-to-day basis.”

Today, the ACC commander must attempt to maintain deployed forces at 85 to 90 percent mission capable but is drawing upon a pool of fighters in which only 75 percent of the fighters are mission capable aircraft. The operational requirement forces “a corresponding [readiness] decline in the forces left in the states,” he said.

With fewer spare parts and technicians, the units left at home have more trouble maintaining their training schedules, which also erodes readiness, Hawley said.

Some units, such as the E-8 Joint STARS surveillance and battle management airplanes, have been so heavily committed during the Kosovo conflict that new crew training had stopped altogether, he said.

In fact, all units remaining in the US “will be undermanned, underexperienced, and they will be flying a very modest training schedule, which will affect the readiness of the aircrews who remain behind,” Hawley warned.

Going Winchester

In his discussion with reporters, Hawley confirmed that, after bombing Yugoslavia for a month, the Air Force had run short of two of its best precision guided munitions.

One of these was the AGM-86C Conventional Air Launched Cruise Missile. USAF B-52s had fired many of the CALCMs in December against Iraq in Operation Desert Fox and then in March and April against Yugoslavia in Operation Allied Force. The expenditure of weapons had left the Air Force “at a point where [it had] to be very judicious in [the] use of CALCMs,” Hawley reported.

Hawley would not give numbers, but a report released by the House Armed Services Committee in late April said there were only about 80 CALCMs left from the total inventory of 250 that existed before the opening of Desert Fox. He noted that the Air Force has signed a contract for conversion of 95 of the old nuclear-armed ALCMs to the conventional versions, but those would not be available until this fall.

Hawley disclosed that the other precision weapon in short supply was the GBU-31/32 Joint Direct Attack Munition, which was dropped by the B-2 stealth bomber with, he said, “great results” during the Yugoslav conflict.

Because the JDAM was a new weapon that was in low-rate production when the conflict over Kosovo started, “we didn’t have a very robust inventory,” Hawley said.

Although production was being accelerated, Hawley warned that it would be “really touch and go as to whether we will go winchester on [run out of] JDAMs before we get the next delivery.”

In his House testimony, Hawley also complained about a lack of precision munitions for training his aircrews, a situation caused by insufficient funding.

“The rules of engagement [for the types of missions being flown in operations such as Kosovo] give us no margin for error putting bombs and missiles on target,” he testified. “That means we have to be very good the first time out, but we don’t have enough training munitions to give our aircrews the practice they need to be that good.”

The erosion of combat capabilities among the augmenting air combat forces and the depletion of the best all-weather precision strike weapons in the battle for Kosovo also would make it difficult for ACC to have provided everything regional commanders might have needed if a war had erupted in the Persian Gulf or Korea, Hawley warned.

With more than 800 US aircraft already committed by early May, the conflict over Kosovo, “is—certainly from an air perspective—this is a Major Theater War,” he said.

Bad News for the CINCs

Hawley maintained that, because significant Air Force capabilities already had been deployed to the Persian Gulf and in Asia, he was “not that uncomfortable with [ACC’s] ability to support either [the regional commander in chief for Iraq or for Korea], if one of those should heat up.” However, he added, “I’d be hard pressed to give them everything they would probably ask for. There would be some compromises.”

Hawley said the Air Force also could have problems activating the Expeditionary Aerospace Force on schedule because units expected to form the first two Air Expeditionary Forces in October could be tied up in the Kosovo operation.

The ACC staff at Langley AFB, Va., he said, was “working hard to make sure we can deploy the AEF concept on the first of October,” he said. He went on, “I think we will. We just won’t be able to fulfill all of the promises that we’ve made to the force on the first of October. That is going to take a little longer.”

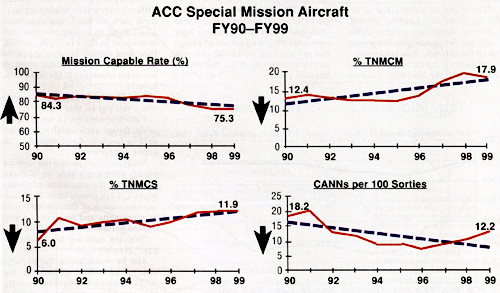

Hawley told reporters that the Air Force was trying to relieve operational pressure on some of its low-density, high-demand aircraft, which included most intelligence, surveillance, reconnaissance, command-and-control, and search and rescue units.

He said the planned delivery of two more RC-135W Rivet Joint electronic surveillance aircraft late this year would help with a force that “has been overcommitted for years.”

He urged an increase in HC-130s, the refueling tanker for the combat search and rescue force and said he hoped the Global Hawk strategic UAV development would succeed because it could complement the U-2s, which also are overcommitted.

In his Congressional testimony, Hawley attributed some of what he called the chronic overtasking of Air Force units to the Goldwater–Nichols defense reforms. The 1980s–era legislation reduced the service chiefs’ ability to control deployment rates. “The result is a tendency for the geographic CINCs and their components to place unconstrained demands on scarce resources,” he said.

The regional commanders in chief cannot balance their demands against the needs of other regions, and the services’ force providers, such as ACC, are prevented by Goldwater–Nichols from making those trade-offs, Hawley told the committee.

“Too many of our warriors are leaving the force, often because they are overtasked,” Hawley warned Congress. “The result of this exodus,” said Hawley, “is inexperienced and undermanned units.”

With those words, Hawley became the first serving senior officer to publicly criticize the Congressionally mandated reforms, which remain popular with the committees that originated them and which enjoy virtual sacred-cow status in the Office of the Secretary of Defense.

Talking with reporters, Hawley said Air Force leaders today are doing a better job than before in drawing on forces worldwide to meet different regional demands. That means Pacific Air Forces units can help carry some of the burden in the Persian Gulf to reduce the strain on ACC, he said. That is done by agreeing within the Air Force on the distribution of the loads and then going to US Atlantic Command, which has ultimate control over most domestic-based forces, to negotiate those allocations with the other regional commanders.

Yet moving forces around to cover gaps is not a solution, Hawley suggested to reporters. He said, “I would argue we cannot continue to accumulate contingencies. At some point you’ve got to figure out how to get out of something.” He noted that US forces have been in Korea for nearly 50 years, have been dealing with Iraq for 10 years, and now has “a significant operation in Europe,” the struggle over the Balkans.

“You just can’t keep forces tied down forever in every one of those contingencies if you are going to continue to accumulate them,” said Hawley. “New ones come in, you’ve got to get rid of some old ones.”

|

| On March 22, Hawley presented the charts on these pages to a Congressional panel. The mission capable rate for fighters (upper left) had dropped to 74 percent in early Fiscal 1998 and remained essentially flat. Trends were negative for “total not mission capable supply” (lower left), “total not mission capable maintenance” (upper right), and “cannibalizations per 100 sorties” (lower right). The Balkan War aggravated the situation. |

|

| ACC’s bomber readiness hit a low of about 65 percent mission capable early in Fiscal 1998, marking a 10-percentage-point drop in just two years. In the first quarter of Fiscal 1999, bomber readiness turned up slightly, to 65.6 percent, but ACC expects the war to wipe out this gain and increase the problems. |

|

| Readiness problems also afflict special mission aircraft such as E-3 AWACS, E-8 Joint STARS, RC-135 Rivet Joint, and U-2 reconnaissance aircraft. The mission capable rate has dropped 9 percentage points in the 1990s, while materiel and maintenance problems have grown dramatically. |

|

| Low pilot retention remains a major readiness problem. The Air Force is headed toward a 2,000-pilot shortage by 2002. The situation is not expected to improve appreciably before 2007, when the force should see the effects of the new 10-year pilot commitment instituted in 1997. |

|

|

|

| Hawley said lower retention created a shortage of journeymen technicians who “should constitute the bulk of the workforce,” and too much maintenance is being done by younger personnel. Some specialties are undermanned. The worst undermanning conditions are found among F-15 and F-16 crew chiefs, F-15 and F-16 avionics technicians, and security forces. |

| ACC in Brief

Air Combat Command, headquartered at Langley AFB, Va., is USAF’s largest major command. It is the main provider of air combat forces to US unified commands. ACC operates fighter, bomber, reconnaissance, battle-management, rescue, and theater airlift aircraft, plus command, control, communications, and intelligence systems. ACC organizes, trains, equips, and maintains combat-ready forces. ACC comprises approximately 91,000 active duty people. Some 63,700 Air National Guard and Air Force Reservists are gained by ACC in time of need. ACC has 1,021 active duty aircraft as well as 763 ANG and Air Force Reserve Command aircraft. Approximately 7,746 airmen have been deployed to the Southwest Asia theater of operations and another undetermined number to Europe for Operation Allied Force. |

| Cohen’s Choice: Cut Deployments or Add Forces

The United States needs a larger military force if it wants to continue operations at the 1990s pace. Defense Secretary William S. Cohen delivered that message in mid-May, first at the Senate Appropriations Committee hearing and then at a Pentagon news conference. He warned that prolonged bombing of Yugoslavia had the potential to deflate the morale of US pilots and other service members. From Cohen’s May 11 committee testimony: “We simply cannot carry out the missions that we have with the budget that we have; there is a mismatch. We have more to do and less to do it with, and so that is starting to show in wear and tear—wear and tear on people, wear and tear on equipment. … “We have a situation where we have a smaller force and we have more missions, and so we are, in fact, … wearing out systems, we’re wearing out people. … “Gen. [Hugh] Shelton [Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff] has talked about the need to relook how the current end strength is structured so that we can put more people into … high-demand jobs where we have … fewer people. But it is a real challenge that we have to watch. We’re either going to have to have fewer missions or more people, but we cannot continue the kind of pace that we have. … “Wherever our people are currently engaged in rather serious operations, you will find that they are most satisfied when they are doing that which they were trained to do. … But if we do it too long, if we do it at such a sustained rate, then the morale will drop off eventually, and it will then reinforce what has been taking place. … “[The troops will conclude,] ‘We can do better on the outside. Life will be easier. I’ll be home weekends or evenings with my wife or husband, and I’ll have a better quality of life with my family.’ That’s the real danger that we face, that we’ve got to find a way to either increase the size of our forces or decrease the number of our missions. … “We have always tried to structure our forces in a way that we could handle two [Major Theater Wars] nearly simultaneously. We have never been structured to handle three. What we have now in Kosovo is roughly a Major Theater War under way. … That means that we’re at three MTWs rather than just two. And so, we didn’t plan for this. “We would have to make a number of adjustments should we ever have another two erupt nearly simultaneously, which we don’t believe will happen but could, theoretically. We would have to make a number of changes then. … “It has been challenging; it has been very difficult on all of our personnel. And that, again, brings us back to the issue. … We have fewer people but more missions. And we have got to make adjustments to bring that back into balance.” From Cohen’s May 12 press conference: “Morale is very high. It’s very high in Aviano, Ramstein, wherever our pilots and crews are operating. What I indicated to the Senate yesterday was that, while it’s high today, if it goes for lengthy periods of time, unless there is some rotation, that can have an impact upon that morale. … “We intend to continue this campaign as long as necessary, and we will rotate the crews as is necessary to make sure that that morale stays at a high rate.” |

Otto Kreisher is the national security reporter for Copley News Service, based in Washington, D.C. His most recent articles for Air Force Magazine, “Next Steps in Information Warfare,” appeared in the June 1999 issue.