At 6:35 a.m. on March 24, 1958, Elvis Presley reported to his draft board in Memphis, Tenn., and was inducted into the Army. He was at the peak of his singing and movie career, but that made no difference. Like many young American men of that day, he had a military obligation to meet.

Elvis took pride in his military service. By all accounts, he was an excellent soldier. After basic training, he served in tank battalions at Ft. Hood, Tex., and in Germany. He was discharged at Ft. Dix, N.J., in 1960 and received a mustering-out check for $109.54.

Draft induction numbers in the late 1950s were down considerably from the level they had reached in the Korean War in the early years of that decade. Nevertheless, a hitch in the armed forces, either as a draftee or a recruit, was still regarded by many as a rite of passage. Young men went when called and served with a generally positive attitude. The day of hard-core draft resistance had not yet arrived.

|

An anti-war demonstrator burns his draft card at a Vietnam War protest outside the Pentagon in October 1967.(Photo by Wally McNamee via Corbis) |

The generation that came of age in the 1950s and 1960s had never known a time when there was no draft. However, the draft that lasted from World War II through the Vietnam War was not in the basic American tradition of military service.

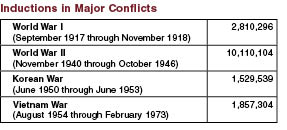

The United States certainly had used the draft at various times in its history; large numbers of soldiers were drafted in the Civil War and in World War I. Still, conscription had always ended when the war did. The draft that began with World War II was different. It lasted for close to 33 years.

Today, conditions could not be more different. The nation has not drafted a single airman, soldier, sailor, or marine in 35 years. Nor is it likely to do so any time soon, for reasons having to do with that last experience with conscription.

In 1936, an obscure Army major, Lewis B. Hershey, was appointed the executive officer of the Joint Army-Navy Selective Service Committee, set up to prepare for possible mobilization. The panel consisted of two officers and two clerks. Hershey was a former schoolteacher who joined the National Guard in 1911 and transferred to the regular Army after World War I. Nobody, least of all Hershey, dreamed the job would last for decades.

No Volunteering Allowed

When Germany in 1940 invaded the Low Countries and France, Congress authorized the first peacetime draft in American history. Inductions began in November 1940. The following year, Hershey was promoted to brigadier general and named director of the Selective Service.

A total of 10.1 million men were drafted during World War II. At the beginning of the war, men rushed to enlist, but, from Hershey’s perspective, that ruined orderly conscription. He persuaded President Roosevelt in December 1942 to end voluntary enlistments except for men under 18 and over 38.

The draft authority expired in 1947, but, even though the Army’s manpower requirements that year were low, recruiters could not meet them. Thus the draft was reinstated in 1948. Draft calls surged at the onset of the Korean War in mid-1950.

The postwar draft restored the option to enlist. Men who could meet the qualification standards could join the service of their choice and get a shot at better training and preferred duty assignments. Draftees had a service obligation of two years, but volunteers served longer tours—four years in the case of the Air Force. Another alternative was to join the National Guard or the Reserve, go to basic training, and then serve out one’s military obligation on training weekends and short active duty tours.

Even in times of conscription, the US military was predominantly a volunteer force. All of the draftees were in that segment of the force with two years’ service or less, and some of the troops in the under-two segment were recruits instead of draftees.

“Historically, inductions accounted for only 30 percent of enlisted manpower,” said Janice H. Laurence in a study for RAND. “The remaining enlisted men were split evenly between true volunteers and those who were motivated to enlist because of the presence of the draft.”

|

Elvis Presley (right) reports with other inductees (Nathaniel Wigginson, center, and Presley’s childhood friend Farley Guy, left) in Memphis on March 24, 1958. (AP photo) |

Most draftees went into the Army. A Presidential panel studying the military manpower issue reported in 1970, “The Navy and Marine Corps have occasionally issued draft calls to meet temporary shortfalls, but the Air Force has never used the draft.”

This was sometimes a cause for complaint. In 1951, Sen. Lyndon B. Johnson (D-Tex.) accused the Air Force of attempting to “skim the cream” off the population of potential recruits. “Men of high intelligence who might have made invaluable officers for the Army are now consigned to the ranks of the Air Force as privates,” Johnson charged.

For its part, the Army came to regard military manpower as a cheap source of labor and wasted it freely on menial tasks such as cutting the grass and painting buildings.

Draft authority was renewed by Congress in 1955, 1959, and 1963 with virtually no debate or opposition. Meanwhile, Hershey and the Selective Service had a new problem on their hands: too many potential draftees. The Army could not possibly use all of them.

Between 1954 and 1964, the number of men eligible for the draft increased by 50 percent while draft inductions dropped from 250,000 to 112,000, respectively, in those years. “We deferred practically everybody,” Hershey said. “If they had a reason, we preferred it, but if they didn’t, we made them hunt one.”

From 1955 on, Hershey and the Selective Service were active in “channeling” men, via deferments, into vocations of national interest. These included science, engineering, medical professions, and teaching. Hershey described channeling as a new major task for the Selective Service.

In 1956, Hershey was promoted to lieutenant general as a result of Congressional pressure and against the wishes of the Army. Although he was officially an Army officer, he had not been responsive to Army control for years. Nor did he defer very much to officials of the various Presidential Administrations. Congressional support gave him an independence similar to that enjoyed by longtime FBI director J. Edgar Hoover or Navy Adm. Hyman G. Rickover.

|

Richard Nixon proposed ending the draft during the 1968 Presidential campaign. Upon taking office, he immediately moved to eliminate the draft entirely. (AP photo) |

An Inherently Unfair System

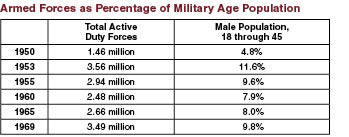

The worst single problem with the draft was that it was inherently unfair. In 1960, the US armed forces’ total strength, counting both draftees and volunteers, was only 7.9 percent of the US male population between the ages of 18 and 45. No matter what, only a fraction of the eligibles were drafted. Furthermore, there was great variation among local draft boards in how they applied the deferment and exemption rules. There was nothing equitable about the system for the minority of the manpower pool who did not escape the draft.

Washington in the mid-1960s made several attempts to establish a draft lottery to spread the risk of induction equally among those eligible for selection. Hershey was staunchly opposed, arguing that decisions by local boards were preferable to “blind chance” with a lottery. Johnson (by then President) and Congress agreed, and the lottery initiatives failed. Also rejected was the idea of setting national standards for local draft boards to follow.

The draft was far from ideal as a source of military manpower. Because draftees served only for two years, it was not worthwhile putting them through long training programs. The technical specialties had to be filled with volunteers.

The Armed Forces Qualification Test (AFQT) ranked scores into five categories, with Category IV—scores in percentiles 10 through 30—being the lowest acceptable for military service. Cat IVs had difficulty absorbing instruction or performing complex tasks, but the draft brought many of them into service.

The number of Cat IVs increased between 1966 and 1971 as a result of Project 100,000, a program introduced by Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara. His aim was to open military service to 100,000 men a year who were otherwise unqualified. By 1969, Cat IVs accounted for 23 percent of inductions.

The draft also brought in a larger number of high school dropouts who, compared to graduates, were only half as likely to complete enlistments. In 1969, dropouts accounted for 27 percent of the enlisted force, ranging from a high of 42 percent in the Marine Corps and a low of eight percent in the Air Force.

More than anything else, it was the Vietnam War that ended the draft. Inductions had fallen to 82,060 in 1962, but then soared to 382,010 in 1966. As draft calls increased, so did the probability that draftees would be sent to combat. Anti-draft sentiment grew, both among military age men and in the public at large. Performances by folksinger Joan Baez featured a banner that read, “Girls Say Yes to Boys Who Say No.”

In time, the burning of draft cards as a form of protest became so widespread that Congress made it a felony. Some draft evaders went to Canada, but the more common way to avoid service was through deferments, exemptions, and disqualifications. Minorities and the poor were the least successful at beating the system this way.

During the 1968 Presidential campaign, Richard M. Nixon proposed ending the draft, and, within days of taking office in January 1969, he took action to reduce the inequities. Secretary of Defense Melvin R. Laird told Nixon that the current requirement was to draft only about a quarter of the eligible men in the manpower pool, and that it would drop to one in seven when the services reverted to pre-Vietnam strength levels.

|

Source: Selective Service Web site. |

Laird proposed a lottery. Hershey was opposed but Nixon agreed with Laird and obtained the concurrence of Congress. The draft lottery was implemented in 1969. At the same time, Nixon appointed the Commission on an All-Volunteer Armed Force with a charter to develop a plan to eliminate conscription. He chose as head of the panel former Secretary of Defense Thomas S. Gates.

“We have lived with the draft [for] so long that too many of us accept it as normal and necessary,” Nixon said.

Hershey, who was opposed to the all-volunteer force (AVF) as well as the other reforms, was clearly part of the problem. Nixon did not hesitate to move against him. He promoted Hershey to four-star general, made him a Presidential advisor, and replaced him as head of the Selective Service. Nixon paid no attention to the advice he then got from Hershey, who eventually was retired involuntarily in 1973 at age 79 and after 62 years of military service.

The Gates Commission made its report in February 1970 and offered three main recommendations as the nation moved toward a volunteer force:

A major increase in military pay.

“Comprehensive improvements” in conditions of military service and recruiting.

Establishment of a standby draft system.

A Hidden Tax-in-Kind

It was clear to everyone that using the AVF would not be cheap, but the commission said that taxpayers at large had gotten a free ride with the draft force. There was a hidden “tax in kind” paid only by draftees and draft-induced volunteers, who were forced to serve for low pay. In 1970, pay for new recruits and draftees was about 60 percent of comparable civilian pay.

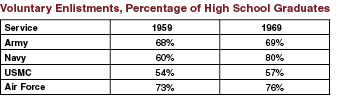

The services had differing experiences. For the most part, Air Force recruiters met their quotas without difficulty through the Vietnam War, although as many as half of the Air Force’s enlistments were induced by pressures of the draft. The Army, though, would have more difficulty with an AVF than the other services.

|

Source: Gates Commission Report. |

The services put more recruiters in the field and hired advertising agencies to support their efforts. To the disgust of many old-timers, a new way of thinking took hold. A 1971 report from the Army’s advertising agency, N.W. Ayer, referred to potential recruits as “the market” and the Army as “the product.” A spotlight fell on Adm. Elmo R. Zumwalt Jr., the Chief of Naval Operations, who achieved fame and notoriety with his programs to (as Time magazine put it) “scuttle those customs and traditions that no longer seem to have a point—if indeed they ever did.”

Upon becoming CNO in July 1970, Zumwalt began sending out directives known as “Z-Grams.” Over four years, he issued 121 of them. An early one eliminated restrictions on the wear of civilian clothes on base when off duty. Another permitted beer-vending machines in enlisted and officer quarters. The most famous Z-Gram was No. 57, issued in November 1970. It said that the “demeaning or abrasive regulations generally referred to in the fleet as ‘Mickey Mouse’ or ‘chicken’ regs had to go.

“We must learn to adapt to changing fashions,” Zumwalt said. “I will not countenance the rights or privileges of any officers or enlisted men being abrogated in any way because they choose to grow sideburns or neatly trimmed beards or moustaches or because preferences in neat clothing styles are at variance with the taste of their seniors.”

Z-Gram 57 allowed sailors who lived off base to travel to and from work in duty uniforms, including dungarees. (Previously they had to wear the uniform of the day or better to travel, change into work uniforms at work, then change again to go home.) It also eliminated the “unreasonable” requirement, for line handlers, refueling parties, topside watch officers in inclement weather, and others, to perform their jobs in white or blue uniforms when “engaged in work which would unduly soil or damage such uniforms.”

Zumwalt encountered opposition mainly from two sources: hard-line admirals and angry chief petty officers. They thought his reforms undermined discipline, and the chiefs did not like it that perquisites it took them years to earn were awarded immediately to junior sailors.

The news media ate it up and made Zumwalt a star. Time magazine said the other services were behind the Navy in getting rid of Mickey Mouse and making “life in the service more bearable and attractive.” The Army reacted with changes that could be made quickly. Among these were an end to unnecessary troop formations, such as assembly at reveille “except for special occasions” and doing away with nighttime bed checks except in disciplinary cases. Ft. Carson, Colo., opened the “Inscape Coffee House” with a black light and a peace symbol on display. Officers dropped by to “rap with the troops.”

|

Lt. Gen. Lewis Hershey is razzed by a small group of demonstrators outside the Selective Service headquarters in 1969. (Bettmann/Corbis photo) |

Not So Much To Fix

The Air Force, with little Mickey Mouse to eliminate, was at a disadvantage in finding things to fix. At a press briefing in December 1970, Lt. Gen. Robert J. Dixon, the deputy chief of staff for personnel, announced that the Air Force was reducing inspections and giving airmen more time off to settle their families when reassigned.

The Marine Corps wasn’t having any of it. The marines said they were going to keep their traditions and their short haircuts and that those who regarded it as Mickey Mouse need not apply.

Incredible though it may seem in retrospect, the burning issue was haircuts. By sheer chance, the coming of the volunteer force issue coincided with the shaggiest men’s hairstyles of the 20th century.

Recruiting ads went as far as they could to appeal to the “market.” When traditionalists complained that the models in the advertising photos violated haircut standards, an Army spokesman explained somewhat lamely that for the soldiers depicted in ads, it was the day before a haircut, not the day after.

Before 1970, Air Force grooming standards had been vague. They said that hair had to be neat and trim, which was sufficient definition for previous generations. In the era of Z-Grams, specificity was required.

The new Air Force standards that appeared in 1970 said that hair could not “exceed one-and-one-quarter inches (11/4″) in bulk, regardless of length.” It went on to explain, “Bulk refers to thickness or depth of hair—the distance the mass of hair protrudes from the scalp when groomed.”

The Air Force ruled that mustaches could not extend any farther than the “vermilion part of the lip” and that sideburns could not “extend below the lowest part of the exterior ear opening.” The other services had sideburn rules, too. Zumwalt wore his own sideburns to the longest length permitted.

Barbers from the base barber shop at Naval Air Station Miramar in San Diego were sent to hair-styling school so they could give a more stylish result with their $1 haircuts.

The uproar about hair and mustaches finally faded away as long hair went out of fashion and hard-liners who insisted on buzz cuts retired from the services. The advertising agency dream of a permissive military gave way to more reasonable goals.

|

The members of the 1972 Joint Chiefs of Staff (l-r): Adm. Elmo Zumwalt Jr., USN; Gen. William Westmoreland, USA; Gen. Robert Cushman, USMC; Gen. John Ryan, USAF; and Adm. Thomas Moorer, USN, Chairman. The services took different approaches to recruit an all-volunteer force. (Bettman/Corbis photo) |

In 1971, Congress approved Nixon’s proposal to “zero out” the military draft but leave the Selective Service machinery in place as a safeguard. Young men would still be required to register with their draft boards.

As the final days of the draft approached, many expressed worry that the AVF would not attract sufficient recruits or that it would pull in only those who could not get a job elsewhere. The National Guard and the reserves, about 75 percent of whose membership stemmed from the pressure of the draft, were of particular concern.

The most frequent problem anticipated, though, was that the volunteer force would not be representative of society at large. It was feared that minorities would bear a disproportionate share of the risk in wartime, with economic incentives to enlist being “tantamount to luring the poor to their deaths.”

The last draft call went out in December 1972. On June 30, 1973, Dwight Elliott Stone, a 24-year-old apprentice plumber from Sacramento, Calif., became the last person to be inducted into the armed forces as a result of the draft.

In July 1973, just eight days after Stone’s induction, Gen. William C. Westmoreland, the former Army Chief of Staff, said, “As a nation, we moved too fast in eliminating the draft.” His 1976 memoir, A Soldier Reports, advanced the view that, without the draft, “the Army might become the province of the less affluent and the less skilled.”

Another opponent of the volunteer force was Sen. Sam Nunn (D-Ga.), who was elected to Congress 1972. Though Nunn’s power in the 1970s was not yet great, the Georgian would eventually become the powerful chairman of the Senate Armed Services Committee.

Some loose ends soon were tied up. President Ford in 1974 gave conditional amnesty to American draft evaders. In 1975, Ford also issued an executive order ending standby draft registration. In 1977, President Carter declared a new broader amnesty for draft evaders and war resisters.

(In 1980, Carter and Congress approved resumption of draft registration in response to the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan. It continues in effect today. Young men are required to register with their draft boards within 30 days of turning 18.)

Proposals to reinstitute the draft have never vanished completely. When repeated cutting of the defense budget in the Carter years led to the “hollow force” of the late 1970s, Gen. Bernard W. Rogers, Army Chief of Staff, and Adm. Thomas B. Hayward, the Navy CNO, called for a return to conscription. The Hollow Force problems were solved instead by the Reagan rearmament programs of the 1980s.

|

Source: Gates Commission. |

A Professional Force

The calamities predicted by critics of the AVF did not occur. Between 1970 and 1973, the number of recruiters increased by 65 percent. Recruits were given better pay, bonuses, and education benefits as well as more latitude in choosing their military jobs. Base pay for the most junior service members almost doubled, bringing it into line with compensation in the civilian sector.

Under the AVF concept, military manpower costs increased by about 11 percent a year, but this never became an affordability problem. The impact diminished as the economy grew and the armed forces decreased in size.

Despite some ups and downs, the services were able to recruit and retain sufficient numbers of high-quality troops. One reason for success was that the number of women in the active duty enlisted force increased from less than two percent when the draft ended to about 15 percent today.

The quality of the force improved, as measured by AFQT scores and educational achievement. The share of the total force holding high school diplomas rose to its highest level ever; at the same time, the number of Cat IV recruits fell nearly to zero.

The Guard and Reserve made the transition well. Selected Reserve strength dropped in the 1970s (nearly all of the fluctuation was in the Army Guard and Reserve) but recovered and reached an all-time high by 1985. With the factor of draft-induced enlistments gone, the Guard and Reserve became more professional and more experienced, at least equal to and often better than active duty forces.

The end of the draft did not lead to a force of the black and the poor. Blacks presently constitute 13 percent of active duty recruits, closely reflecting the US military age population, which is 14 percent black. Blacks are 19 percent of the active duty enlisted force, the exact percentage predicted in 1970 by the Gates panel. Neither minorities or the poor have been overrepresented in the combat arms or in the fatality rates in combat.

The clamor to bring back the draft rose again in 2003. However, this time it was led by a staunch liberal, Rep. Charles B. Rangel (D-N.Y.). Rangel particularly deployed the allegation—refuted with strong evidence by the Pentagon—that the volunteer force puts too much of the burden on minorities and the poor.

The circumstances under which the nation would accept a revival of conscription after a hiatus of 35 years are unknown. What is clear, however, is that recent circumstances have not been sufficient. Rangel’s proposal went essentially nowhere. In October 2004, the House rejected it by a vote of 402 to two.

John T. Correll was editor in chief of Air Force Magazine for 18 years and is now a contributing editor. His most recent article, “The Air Mail Fiasco,” appeared in the March issue.