In recent times, Air Force combat operations in Southwest Asia underwent a dramatic change—two changes, to be precise. And therein hangs a tale about the value of expeditionary airpower, as currently generated by American airmen.

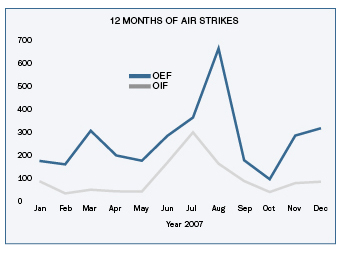

The first change began in the summer of 2006. The number of attacks against enemies in Afghanistan began to soar. They peaked in August 2007, when USAF air crews conducted 670 close air support strikes. In Iraq, a similar buildup of air activity began early in 2007, just as the US opened its “surge” of ground forces into the country. USAF’s combat missions in Iraq spiked in July 2007, a month in which the force mounted 303 devastating CAS attacks against Iraqi insurgents.

Then came the second change. The number of strikes since summer underwent a sharp drop. In Afghanistan the number of CAS strikes fell to 98 last October, the lowest number since mid-2006. In Iraq, the story is much the same.

|

A B-1B, which has been a heavy hitter in the War on Terror. (USAF photo by Capt. Justin T. Watson) |

Does this mean that airmen now have withdrawn from the fight? Hardly. The number of combat air strikes may rise or fall over any given period, but the Air Force’s overall level of effort—combat, intelligence-surveillance-reconnaissance, mobility, and other missions—has remained constant. Requirements are stable.

What the sliding scale of air attacks did show—in spades—was the enormous flexibility, power, and agility of USAF’s 27,000-man force in the region. This air legion was able to go from a virtual standing start and, without any great augmentation, take on greatly expanded combat activity.

Put a different way, it was a surge in power without a need for a surge in manpower.

This capability didn’t appear by accident. The nation’s airmen have worked hard for years to create such a force.

USAF’s network of six expeditionary wings and other forward bases is now highly refined. More than 5,000 airmen are forward based at Balad AB, Iraq. Another 5,000 are at an undisclosed location in Southwest Asia that hosts the Combined Air Operations Center and the 379th Air Expeditionary Wing.

(Several operating locations are not discussed publicly, at the host nation’s request.)

The rotational assignment system of the Air and Space Expeditionary Force (AEF) keeps nearly 3,000 airmen at Bagram AB, Afghanistan; 2,000 airmen with the 386th AEW in Southwest Asia; 1,500 airmen with the 380th AEW at a third undisclosed location; and 1,000 airmen at Baghdad Airport.

The Air Force is moving to enhance its infrastructure at four bases. USAF’s theater engagement strategy calls for developing long-term, stable relationships in the Middle East, and the Air Force is only present at bases where it is wanted.

The homes of the 379th and 380th AEWs are being beefed up, as are Balad and Bagram. The CAOC is currently housed in a thin-skinned converted medical warehouse; a new air operations center will be built there. A former ground equipment warehouse at the same base has been converted to storage for B-1 parts to support the bombers there.

At Bagram, lack of space is becoming a problem. The ramps and building spaces are now essentially full.

|

An A-10 prepares to gas up for a combat mission in Operation Enduring Freedom. When combat needs changed, some A-10s shifted from Iraq to Afghanistan. (USAF photo by Lt. Col. Marcel Dionne) |

The CAOC supports operations in three distinct zones—Iraq, Afghanistan, and the Horn of Africa. Air assets swing between theaters as needed. US Central Command Air Forces officials say airpower must remain flexible to meet ground commander needs.

USAF is flying roughly 150 sorties a day over Iraq, half of which are counter-IED missions, designed to thwart enemy use of improvised explosive devices. Targeting-pod-equipped fighters have proved adept at this mission. Except for the B-1B bomber, all USAF combat aircraft operating over Iraq are now fitted with targeting pods.

The B-1Bs will be adding pods in mid-2008, but they already offer a significant capability in the theater. Col. Michael D. Rothstein, CENTAF operations director, said the bombers can hang out for six to eight hours over a target area and deliver 20 bombs on a target—or a single bomb on 10 different targets. The B-1Bs, based at a single location in theater, swing between Iraq and Afghanistan as needed.

High Tech, Low Tech

Officials are also looking forward to bringing laser guided Joint Direct Attack Munitions to the theater this summer. The laser JDAMs will offer satellite guided all-weather accuracy and the ability to hit moving targets.

Pilots have been using AGM-65E Maverick missiles with laser spotters as an “interim solution” for moving targets. It’s been pretty effective. Example: A Maverick recently wiped out a pickup truck with a machine gun mounted in the back, used by Iraqi insurgents against US ground troops. In another instance, a USAF pilot, using an AGM-65E, obliterated a heavy-duty construction front loader that had run through two checkpoints while carrying a large load of explosives.

The wars remain a mix of high and low tech. The Air Force’s Reaper unmanned aerial vehicle made its combat debut last fall. “I’ve got two of them flying in Afghanistan right now,” said Lt. Gen. Gary L. North, commander of US Central Command Air Forces and combined force air component commander. “They’re flying as programmed [and] doing incredible work.”

Officials may send a batch of Reapers to Iraq next year to complement the manned fighter squadrons there. CENTAF could then “perhaps send a manned squadron home from the theater,” North said.

“We are seeing instances already where Reapers are coming back Winchester”—having fired all of their missiles at targets in Afghanistan, said Lt. Col. Wayne Straw, director of the CENTAF commander’s action group.

While these remotely controlled flying robots are firing precision missiles, another, decidedly old-school weapon has made a comeback. “Twenty-five percent of every weapon we employ is a bullet,” said North.

Airpower’s flexibility has been significant. CENTAF had to implement a “significant number of workarounds” to offset a temporary F-15E grounding last fall. Planners looked across the theater to find the needed assets. “What we did was we picked up and moved an A-10 unit from Iraq back to Afghanistan,” North said.

Col. Gary L. Crowder, deputy CAOC director in Southwest Asia, noted that A-10s were first based in Iraq early in 2007 to support the surge, and then were shifted to Afghanistan in the middle of their deployment to provide extra firepower when the Strike Eagles were grounded.

CENTAF also got larger contributions from coalition and naval aircraft, and left the F-15Es on ground combat alert. The Strike Eagles were launched several times during the general grounding, to support troops who had come under attack.

“In one of the cases where we launched them, we had a unit in the 82nd Airborne that was very heavily engaged, and the ground commander told me that if we had not launched the airplanes he probably would have lost his whole unit,” North said.

The Warthogs and F-15Es remained in Afghanistan in late 2007, while the number of F-16s in Iraq has increased.

|

SrA. Shiloh White Hawk oversees a hydrant pumping fuel into a KC-10 at a base in Southwest Asia. (USAF photo by MSgt. Ruby Zarzyczny) |

One of the initial drivers behind the AEF concept was the need to spread the pain during the days of the no-fly zones over Iraq in the 1990s. Small numbers of air superiority and other select units found themselves deployed to the desert over and over again.

The AEF system creates a much larger base of airmen to draw from and builds in training and recovery time, plus predictable schedules for many—but certainly not all. The high-tempo career fields have changed and now include CAS units, security forces, and special operators.

“In Lieu Of” Missions

SrA. Michael Newton was at the high end of the deployment spectrum. A high-demand explosive ordnance disposal technician with the 20th EOD Flight at Shaw AFB, S.C., Newton was back from a three-month stay at Balad last fall. His experience reflects the larger trends—Newton said that at the beginning of his deployment, he was disarming IEDs almost every day. Toward the end of his tour, the number of explosives needing to be disarmed “began to taper off.”

Airmen continue to work closely with the Army on the ground, sometimes in their natural roles for missions such as terminal air control, and sometimes on temporary assignments to help the Army move more soldiers in ground combat missions.

Despite concerns about the practice at the highest levels of the Air Force, the number of airmen performing “in lieu of” missions for the land components has nearly tripled in the past two years. Less than 2,000 airmen were performing ILO missions such as interrogator and convoy driver in 2005. The number is now over 5,000.

The rotations are reaching into new areas of the Air Force. In the fall, the 20th Fighter Wing at Shaw was preparing for its first AEF deployments in years. Shaw has traditionally focused on the suppression of enemy air defenses mission (not a priority in post-2003 Iraq), and its fighters were recently upgraded.

The 20th was tapped to relieve some of the burden on USAF’s traditional close air support units, explained Col. James N. Post III, wing commander.

The wing’s three squadrons of F-16CJs will deploy sequentially. The 79th Fighter Squadron will head to the Pacific region, and then the 77th and 55th squadrons will take turns in Southwest Asia, probably in Iraq. Post said the airmen have been building up their CAS skills through advanced training, deployments to Red Flags, and other measures.

Although their destination had not been announced by press time, Capt. Nathan Diller of the 79th FS said his squadron’s training focus has been on the close air support requirements needed for the Korean Peninsula.

Capt. Bill Lutmer, an F-16 pilot with the 77th FS, said pilots have been working with Sniper targeting pods to build the skills needed in the desert. “Toward the end,” he said, the training is expected to be “all CAS.”

The pilots aren’t the only ones getting ready for overseas tours. SMSgt. Mike Gilder, maintenance flight chief at Shaw, said maintainers start preparing for deployments at least six months ahead of time, and knock out scheduled inspections in advance. “We don’t want broken jets on the flight line,” in the war zone, he said.

Officials noted that once overseas, CENTAF’s aircraft have the highest priority for spare parts, so wartime reliability has not been an issue in theater even for geriatric aircraft such as the KC-135 and C-130.

|

The tempo is extremely high in the desert. North said deployed F-16s fly at 5.8 times the normal rate, and F-15Es at four times the “peacetime” rate. The effect is mitigated by the AEF rotations, but a Viper on a four-month assignment to Iraq still accumulates nearly two years’ worth of flying hours.

This war zone emphasis has a trickle-down effect, and further damages the reliability of old airplanes at their home stations, where parts are not as readily available.

Neighborhood Watch

In Iraq, the surge allowed US forces to increasingly move out of their main operating bases and into neighborhoods, affording them greater opportunity to interact with the Iraqi population. This has helped build trust and develop local support. Attacks on US forces are way down—even though there are now more Americans for insurgents to target.

In both theaters, airborne and ground intelligence continues to improve. Intelligence aircraft are overhead around the clock, and coalition forces have “wrapped up so many bad guys, either killed or captured,” that the success now builds on itself, said North.

Predators, U-2 spyplanes, and other intelligence collectors are providing the “unblinking eye” over the battlespace that allows the Air Force to track suspected terrorists for extended periods and learn their habits, contacts, and routines. North spoke highly of the U-2’s utility. “We are able to cross-cue these ‘Cold War’ systems that have been modified for the current war,” North said, so that they can communicate directly with other aircraft and the joint terminal attack controllers on the ground. The days of film canisters are long gone, and today the end users have access to U-2 reconnaissance in near real time.

Meanwhile, three airmen working in intelligence units at Langley AFB, Va., and Wright-Patterson AFB, Ohio, “came up with a way to more efficiently align the patterns of these U-2s, and by doing that we are able to increase our take by 40 percent,” North said. “Unbelievable.”

Because of the Air Force’s constant presence overhead in Iraq, the enemy fights in very small groups. They “shoot and scoot, use a lot of IEDs,” North said. Insurgents rely on sniper and mortar attacks, and are often protected by urban surroundings. These tactics mean that the insurgents in Iraq are not presenting themselves as attractive targets, but it is similarly difficult for them to achieve anything of substance.

|

C-130s such as this one (overflown by Black Hawks) play a vital role air-dropping supplies to forward based troops. (USAF photo by SSgt. Joshua T. Jasper) |

The same is not true in Afghanistan. “People try to correlate what we do in Iraq with what we do in Afghanistan, and, frankly, [they are] two completely different wars,” said North.

The scheme of maneuver is “completely different,” North said. In Afghanistan, “the enemy presents in larger numbers, and is not as skilled as some of the enemy in Iraq.” The country is also less urban, eliminating many of the collateral damage concerns that can restrict air strikes in Iraq.

Terrorists have been able to hold some territory in Afghanistan, but this has come at a high cost. CENTAF officials noted that 2007 was the deadliest year yet for insurgents in Afghanistan.

Supplying the forward bases, moving troops around, and refueling a 24/7 overhead presence are USAF’s mobility forces. Brig. Gen. Alfred J. Stewart, who in December was serving as the director of mobility forces at the CAOC, noted that 70 percent of the sorties on CENTAF’s daily air tasking order are mobility missions. This includes the movement of 3,000 passengers on a typical day (more than 500 detainees were relocated by air one day in early December), and the refueling of some 200 different US Air Force and other friendly aircraft.

|

At a base in Southwest Asia, A1C Daniel Morton secures a bomb to the ram jammer operated by A1C David Pownell. Some combat aircraft, such as this B-1B, can reach both Iraq and Afghanistan from a single expeditionary base. (USAF photo by SSgt. Douglas Olsen) |

KC-135s from one forward base are airborne at all times to meet the demand—and because there is not enough parking space for them all to be on the ground at once.

In Afghanistan, airdrops are growing in importance. US and NATO troops are increasingly moving into remote, high-altitude areas completely inaccessible for ground resupply. The 475 OEF airdrops in 2007 were a 13 percent increase over the year before.

Up in the mountains of Afghanistan there are now dozens of small forward operating bases. Those troops “can only survive in those high hills being resupplied by air,” said North.

Stewart said the airdrop effectiveness in Afghanistan is nearly 100 percent. The Air Force doesn’t want forces to have to “chase their supplies” while operating in dangerous territory, he said.

Large mobility aircraft are increasingly operating from the theater. Stewart said more than 40 tankers are stationed around the area of responsibility, along with 20 C-17s. Some of the tanker crews fly so many hours that they have to be replaced by fresh pilots halfway through their four-month AEF tours—the aircraft stay in theater.

Mobility is a Total Force effort. In December, all of the C-130s operating out of Bagram Air Base were Air National Guard aircraft.

The overall numbers of tanker, ISR, and airlift sorties have remained relatively stable from year to year. Even with the end-of-year declines, however, 2007 was a very kinetic year for CENTAF.

In 2007, air strikes in Iraq tripled the previous high since the end of major combat operations in 2003. Afghanistan’s CAS strikes steadily ramped up from 86 in 2004 to 176, then 1,770, and finally to 3,247 in 2007.

Numbers Can Deceive

Ground forces are now deployed in larger numbers, are generally closer to the fight, and have suffered the majority of casualties in the War on Terror. The air component’s contributions are often behind the scenes, overlooked, or hard to put in context.

The numbers can obscure the big picture. Maj. Gen. Maurice H. Forsyth, deputy CFACC, notes that even the daily airpower summaries put out by the CAOC can leave airpower’s significance unclear.

Forsyth “often challenges the CAOC staff to look at the statistical data being presented and say, ‘So what?'” officials acknowledged last fall. “The numbers are great, but what is the true impact? What progress is being made?”

Two case studies—one from Iraq and one from Afghanistan—help illustrate airpower’s contribution.

|

F-15Es, such as this one from RAF Lakenheath, Britain, have long been an important factor in the war in Afghanistan. (USAF photo by SSgt. Craig Seals) |

On Sept. 25, coalition aircraft flew 53 CAS missions in Iraq. These included Air Force F-16s striking an enemy building with laser guided bombs, according to the day’s airpower summary.

So what? That particular mission destroyed a safe house where Abu Nasr al-Tunisi, a leader of al Qaeda in Iraq, and two other operatives were meeting, killing all three.

ISR assets will follow individuals or groups for extended periods. “We wait and we plan, and we will find the time” to send in forces to capture or kill the target, North said.

Many successful operations are now coming directly from tips from concerned Iraqis. According to Multinational Force-Iraq officials, most high-profile terror attacks in Iraq, and 80 percent of the suicide attacks, are conducted by foreign terrorists. Al-Tunisi, for example, was Tunisian.

“An event like that is a visual depiction of success, when many times success is difficult to see,” said Forsyth. Contributing to this particular operation were F-16s, joint terminal attack controllers on the ground, unmanned aerial vehicles, and space systems—satellites pass over War on Terror targets 560 times a day.

Then, in mid-December came an example from Afghanistan.

|

F-16 fighters, such as these on the flight line at Balad AB, Iraq, have become the workhorses of air operations over Iraq. (USAF photo) |

Afghan and NATO forces, greatly supported by US airpower, moved into the town of Musa Qala on Dec. 10 and recaptured the town the following day. British forces previously protecting the town had vacated it a year ago after brokering a deal to hand over security to the locals.

The Taliban promptly moved in and seized the town in February 2007, shortly after the British withdrawal. The Taliban turned Musa Qala into a stronghold in Afghanistan’s contested Kandahar region.

By late 2007, enough was enough and NATO and Afghan National Army forces moved to recapture the town. CENTAF provided “the majority of the kinetics,” for the days-long operation, North said. A-10 Warthogs, Apache attack helicopters, and airdropped US paratroopers all helped recapture Musa Qala, which was the last town of any significance held by the Taliban.