First Lt. Patrick Wynne, a United States Air Force pilot, perished in 1966 in the Vietnam War. He had been flying on Aug. 8 in the backseat of an F-4C during a dangerous raid over North Vietnam. Wynne and the F-4’s pilot, Capt. Lawrence H. Golberg, were shot down north of Hanoi, near China.

Wynne, a 1963 graduate of the Air Force Academy, died wearing his class ring. Though his remains were returned in 1977, his ring was not. It was, in fact, missing and all but forgotten until last year. Then, in an astounding turn of events, it was handed over to a former Secretary of the Air Force—Michael W. Wynne, Patrick’s younger brother.

|

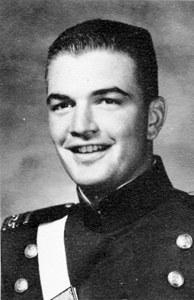

Patrick Wynne, shown here as an Air Force Academy cadet, Class of 1963. |

This is the story of how that ring, having been in China for four decades, found its way back to the Wynne family.

On that fateful day in 1966, 24-year-old Patrick Edward Wynne volunteered to fly one of the most hazardous missions yet assigned to the 555th Tactical Fighter Squadron, stationed at Ubon RTAB, Thailand. As a “GIB” (guy in back), Wynne was eager to accumulate flight time and move to the front seats of the husky McDonnell Phantoms flown by his unit. For this mission, Golberg’s backseater was ill, so Wynne took his place in F-4C serial No. 63-7560.

A superstitious person might have noticed that the flight was Golberg’s final scheduled mission. On its completion, Golberg was to receive the customary celebratory wet-down before being sent back to the United States. The intensely competitive Wynne was not the least bit superstitious, however.

Patrick Wynne entered the Air Force Academy determined to graduate with a ranking higher than his father, Edward P. Wynne, had achieved at West Point in 1940. The younger Wynne did so, finishing in the top 10 percent of his class. He received his diploma from Gen. Curtis E. LeMay, the legendary airman who was then the USAF Chief of Staff.

After graduation, Wynne filled the time awaiting pilot training by earning a political science degree from Georgetown University in Washington, D.C.

Young Wynne excelled in flight school, driven by his determination to be a fighter pilot. He won his wings and sought duty in Vietnam. He served with the 555th for only four months, but Patrick was soon noted for his cheerful and relentless push to fly every mission he could.

|

A close-up of the USAFA class ring recently returned to the Wynne family. |

Few missions in the Vietnam War were more difficult than that assigned Ozark Flight on that August day in 1966. The orders called for four Phantoms to fly a minimum-level armed reconnaissance mission in Route Pack 6, with the target area 30 miles north of Hanoi. Each Phantom was armed with four pods of CBU-2 cluster bombs and four Sparrow and Sidewinder missiles.

The Ozark Flight

The eight crew members were surprised to learn that their sorties were routed to the target from the coast. This meant the fighters would have to fly over one of the most heavily defended regions in North Vietnam. The previous morning, six fighters had been shot down in exactly the same area.

Ozark Flight, Capt. Daniel Wright leading, was launched on time and climbed to 21,000 feet for its first refueling over the Gulf of Tonkin. Only three aircraft were able to take on fuel. Ozark 2, flown by 1st Lt. John H. Nasmyth, could not get his refueling door to open. He had to return to base.

(This may have looked like Nasmyth’s lucky day, but he was shot down less than a month later. He spent six years as a POW. His backseater, 1st Lt. Raymond P. Salzarulo Jr., was killed.)

The remaining Ozark aircraft flew in echelon right with Wright still leading. Maj. John Hallgren moved into the No. 2 position, with Golberg and Wynne off his right wing. The three Phantoms dropped down to a mere 50 feet above water so as to penetrate North Vietnam’s airspace beneath its radar screen. Going “feet dry” 40 miles north of Haiphong, Ozark Flight initially met no resistance.

|

Former Secretary of the Air Force Michael Wynne examines his older brother’s ring. |

The Phantoms found few meaningful targets in the assigned area, but, returning on the reciprocal course, the fighters destroyed some trucks with their cluster bombs.

The flight then dropped over a sharply defined karst limestone formation down into a lush valley. The airmen suddenly were enveloped in a barrage of 37 mm and 57 mm anti-aircraft fire. Hallgren took heavy flak hits in the lower rear of his F-4’s fuselage; it knocked out his hydraulics and set off a number of red lights in the cockpit. Golberg radioed that he too was hit. Hallgren saw him pull up and drop back, calling that he had control problems. Hallgren advised Golberg to check his stability augmentation system. He then lost sight of Golberg and Wynne’s aircraft.

Ozark 1, Wright’s aircraft, returned to Ubon. Ozark 2, streaming fuel and in obvious distress, nevertheless managed to make a brakeless landing at Da Nang, saved by arresting gear.

Ozark 3, with Golberg and Wynne, disappeared into the jungle. Their last known location was 21 degrees 33 minutes north latitude and 106 degrees 46 minutes east longitude—near the village of Lang Son, just south of China.

Golberg and Wynne were listed as missing in action until 1976, when their remains were found and identified. These were returned in 1977. Wynne was buried at the Air Force Academy. Golberg was buried in Minnesota. The government changed their status from MIA to killed in action, and their two names were engraved on the black granite of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial wall in Washington, D.C.

The story was far from over, however.

Everyone had always assumed that the two men had died instantly in the crash of the F-4. When specialists were able to conduct an examination, however, they discovered a fracture in the bone above one of Wynne’s knees. They could only conclude from this evidence that Wynne had managed to eject.

The unknown story was that Patrick Wynne, though badly injured, had survived the ejection. He was soon found by a rural Chinese family, living in North Vietnam. They cared for him in his final hours of life. When Wynne died, the family retained his Air Force Academy ring with the intention of somehow returning it to his family.

It took more than four decades, a strange coincidence, and the goodwill of an American businessman for the Chinese family to fulfill its intentions. The story unfolded this way:

After the war, Washington established formal ties with the People’s Republic of China. In 2005, Consortium Companies, Inc., of Erlanger, Ky., opened a satellite office in Guangzhou, China. Consortium Companies sent Herbert G. Schaffner to Guangzhou in August 2007 to serve as director of information technology at this southern China office.

Schaffner, the son of a Vietnam veteran, married a Chinese woman. At a family celebration, he was introduced to her uncle. At the time of Wynne’s crash in 1966, this uncle was only 10 years old. He related a poignant story to Schaffner. The uncle’s family had relocated to North Vietnam to earn a living farming just as the Vietnam War started to intensify. The family had become accustomed to seeing American aircraft flying over, and when they saw an intense fire in the distance, they knew that an airplane had been shot down.

A Long Trip Home

The narrating uncle’s father went to investigate, found a badly injured American pilot, and brought him back to his village to be cared for. The family tried to save the young man’s life, but failed. (This family wishes to remain anonymous, perhaps out of concern for the consequences, even now, of having aided the enemy airman.)

|

The aircraft symbol marks the spot near the southern Chinese border where Ozark 3 crashed into the jungle. |

At this point, the story becomes murky. It is not clear whether Wynne, before he died, was taken into custody by North Vietnamese officials. What is certain is that the Chinese family recognized the sentimental importance of Wynne’s ring, and retained it with the intention of somehow getting it back to his family.

The father who found Patrick Wynne gave the ring to the uncle. The uncle later found a translator who read the name inscribed inside the ring: Patrick Edward Wynne. He took the ring to the US Consulate in Guangzhou, in hopes of learning more about the deceased’s identity. However, he received no aid.

When the uncle learned that his niece had married Schaffner, he asked Schaffner for help. Schaffner immediately identified it as a ring of the Air Force Academy’s 1963 graduating class. He took it to his company’s headquarters in Kentucky on his return to the United States. The firm’s chief financial officer, Roger Schreiber, looked further into the matter and discovered that the dead pilot’s brother had just stepped down as the Air Force’s top civilian leader.

It was fall 2008. Schreiber placed the call.

Michael Wynne was overcome. Patrick had been shot down on the very day that the future Air Force Secretary had signed in at his first USAF duty station—Hanscom AFB, Mass. Now, just after leaving as Secretary of the Air Force, Michael Wynne said it felt as though “my brother was reaching across the decades.” Patrick’s widow, Nancy, also was notified of the ring’s return.

|

|

For years, the Wynne family had wondered about the circumstances surrounding Patrick’s death. Now, 42 years later, essential parts of the story, and Patrick’s ring, were recovered. Wynne was relieved to know that kind people had cared for his brother at the end of his life.

At reunions, the Class of 1963 gathers for a toast; they ceremonially turn upside down the cups of deceased. This takes place in the office of the president of the Association of Graduates. More than a decade ago, Michael Wynne added to the office wall a plaque detailing the story of his brother, up to the point of the shootdown. Now the story can be told in full.

The Wynne family has decided to return the ring to the academy as well. It will be housed in a small shadow box. The former Secretary said he hopes it will be permanently displayed in the Association of Graduates building, marking the end of a truly amazing journey.