–

The centerpiece of the Arc Light memorial on Andersen AFB, Guam, is a B-52D bomber, painted in jungle camouflage and with markings from the Vietnam War. It is dedicated to the B-52 crew members who lost their lives in that war. Their names are engraved on a bronze plaque at the memorial.

In a larger sense, the memorial recalls the long-running B-52 combat operation, code-named Arc Light, that encompassed more than 126,000 sorties over Southeast Asia between 1965 and 1973. Andersen was Arc Light headquarters and the principal base, but B-52s also flew from two other bases—U Tapao in Thailand and Kadena on Okinawa.

|

Andersen AFB, Guam, during the Arc Light era. (USAF photo via Lt. Col. George Allison) |

The B-52s unquestionably brought the most lethal firepower of the war but much of the Arc Light employment, especially in the early years, was against minor targets in support of ground operations in South Vietnam. However, Arc Light culminated in Linebacker II, the 11-day bombing of North Vietnam in 1972 that led to the end of the war. It was an indication of how the US venture in Southeast Asia might have turned out had it been fought with a different strategy.

Arc Light was not part of the Vietnam air campaign run by 7th Air Force in Saigon. The Arc Light crews were drawn from the Strategic Air Command nuclear alert force and, wherever they were, they remained under control of SAC.

From beginning to end, Arc Light was executed by aircrews and ground crews from SAC bases in the United States on temporary duty rotations up to 179 days. Anything longer would have triggered a permanent change of station reassignment from their home wings. Some of them pulled half a dozen Arc Light tours or more, amounting to more than 1,000 days. They did not get credit for a Southeast Asia combat tour.

Sledgehammers and Gnats

Nothing like Arc Light had been anticipated. The B-52, operational since 1955, was SAC’s principal long-range, deep penetration nuclear bomber. It could deliver conventional ordnance, but SAC was not enthusiastic about that. In 1964, the Joint Chiefs of Staff directed that 30 B-52s be kept available for worldwide contingencies.

In February 1965, as the Vietnam War heated up, 30 B-52s deployed from the United States to Guam and KC-135 tankers were sent to Kadena to support them. The JCS recommended striking North Vietnam with B-52s, but that was ruled out as too provocative by the State Department and the White House. SAC wanted to bring them back home, but was not permitted to do so. They did not remain idle for long.

Gen. William C. Westmoreland, commander of Military Assistance Command Vietnam, persuaded the JCS to use these B-52s against Viet Cong base camps in South Vietnam. Earlier strikes by tactical aircraft had been unsuccessful, and the B-52s could put down an even pattern of bombs over a large area.

The first Arc Light mission was flown from Andersen on June 18, 1965 by B-52F crews on rotation from Carswell AFB, Tex., and Mather AFB, Calif. There were numerous last-minute changes, a complication that would become familiar in the years ahead. To calm White House fears of bombs hitting friendly troops or civilians, an Air Force brigadier general from Saigon was dispatched to the target area to keep watch in a C-123 command and control aircraft.

|

A B-52D from the 93rd Bombardment Wing drops a stream of 500-pound bombs. (USAF photo) |

Everything went wrong on that first mission. The B-52s reached the refueling area seven minutes early because of tailwinds from a typhoon. The first aircraft to arrive was flying a circular holding pattern and collided with another aircraft just getting there. Both fell into the sea. The other B-52s completed the mission but the intended target, a Viet Cong battalion, was gone before the bombing started.

Time Magazine equated the Arc Light missions to “using a sledgehammer to kill gnats,” but the commitment persisted. Operations were initially limited to South Vietnam as the Administration worried about escalation to “a wider war.”

Command and control remained with SAC, but MACV could nominate targets. Westmoreland’s method was to use B-52s as heavy artillery. He also liked their psychological effect on the enemy. The first indication the Viet Cong had that the B-52s were there was when the jungle erupted around them.

Gen. William W. Momyer, commander of 7th Air Force, was “appalled by the enormous tonnage of bombs the B-52s were dropping on the South Vietnamese jungle with little evidence of much physical effect on the enemy, however psychologically upsetting to enemy troops in the vicinity,” said Air Force historian Wayne Thompson. However, Gen. Lucius D. Clay Jr., commander of Pacific Air Forces later in the war, acknowledged that the B-52s “gave ground forces the kind of fire support no other army has ever had.”

In December 1965, Arc Light was expanded to include the Laotian panhandle, and the first strikes in North Vietnam, just over the border, were in April 1966. By the middle of 1967, the B-52s had established a sortie rate of 800 a month.

Airmen of the Vietnam era called Guam “The Rock.” It is the largest island in the Marianas, a 32-mile-long column of basalt and limestone rising out of the Mariana Trench. Andersen, located at the north end of the island, was formerly North Field, built for B-29 missions against the Japanese home islands in World War II.

Before Arc Light, SAC had kept a small force of B-52s on Guam on “reflex alert.” The first Arc Light missions were controlled by the existing organization at Andersen, but SAC soon formed provisional wings—and in the later phases of the war, provisional air divisions, at both Andersen and U Tapao—to which B-52 crews and support elements from US bases could be attached. Third Air Division, the longtime SAC headquarters on Guam, controlled all SAC operations in Southeast Asia until 8th Air Force relocated to Guam in April 1970 and took over.

Andersen has two parallel runways. The prevailing wind is such that virtually all takeoffs and landings are to the northeast. The runways end at Pati Point, where a cliff falls 500 feet to the sea. Throughout the Vietnam War, a Russian trawler lay off Pati Point, watching the takeoffs.

The Andersen runways are famous for the dip in the middle, which creates an uphill stretch toward the northern end. “On takeoff to the northeast, speed came up rather rapidly on the downslope but the upslope took a toll in speed so that it merely crept up towards liftoff numbers,” said retired Lt. Col. Charles D. McManus, an Arc Light veteran who now lives on Guam.

From Andersen, it was 2,600 miles to Saigon. The round-trip mission lasted 12 to 14 hours. The B-52s flew in loose, three-ship formations to a refueling point north of the Philippine island of Luzon and refueled over the South China Sea. On return, they flew directly east across the Philippines to Guam.

A second Arc Light base was established in 1967 at the Thai Navy airfield at U Tapao on the Gulf of Siam. It was initially a shuttle bombing base. B-52s took off from Andersen, flew their missions, recovered and rearmed at U Tapao, flew another mission and returned to Andersen. In 1969, U Tapao was upgraded to a main operating base. U Tapao was closer to the targets; the missions were only one-third as long as those launched from Guam, and there was no need for aerial refueling.

|

This B-52 on display at Andersen AFB, Guam, serves as a memorial to Arc Light. The original “Old 100” was damaged and replaced with this one in 1983. (Photo by Ted Carlson) |

“Old 100”

When the American Tet counteroffensive got into full swing in February 1968, SAC also began staging Arc Light missions from Kadena.

In the earliest days, the first missions were flown by B-52Fs, which carried 27 bombs internally and 24 more on wing racks. B-52Ds took over in 1966 and became the signature bombers of Arc Light. They were older than the Fs, but with the high-density bombing or “Big Belly” upgrade, they could carry 84 bombs in the bomb bay and another 24 on pylons.

One D model nicknamed “Old 100″—serial number 55-0100—flew 5,000 combat hours. It was displayed at the Arc Light memorial until 1983, when corrosion from the salty air and damp climate of Guam forced its replacement with another B-52D. The replacement aircraft, painted with “Old 100” markings, was itself a veteran of numerous Arc Light sorties.

During the Arc Light maximum effort in 1972, B-52Gs joined the operation. They had longer range, but carried only 27 bombs. The newest of the B-52s, the H models, never flew in Arc Light.

When Arc Light began in 1965, the B-52s were painted for the strategic nuclear mission. The reflective anti-flash undersides of some of the B-52Fs were overpainted with black to reduce visibility at night. The B-52Ds introduced the characteristic look of Arc Light, with top surfaces painted jungle camouflage, tan, and two shades of green.

The standard strike formation for the Arc Light B-52s was the three-ship “cell.” The attack could be either by a single cell or multiple cells, the combination being known as a “wave.” Bombing altitudes were typically 25,000 to 30,000 feet. The targets were area boxes 1.2 miles long and .6 miles wide, which the B-52s could saturate with high explosives. By June 1967, Arc Light made extensive use of ground-directed radar bombing. Seven radar sites covered all of South Vietnam, eastern Cambodia, southern Laos, and the southern part of North Vietnam, and, from 200 miles away, guided the bombers precisely to the release point.

The enemy rarely grouped itself into mass formation, but when it did, the effectiveness of the B-52s was overwhelming. One such instance was the battle of Khe Sanh during the Tet Offensive of 1968.

Khe Sanh was a combat base situated 15 miles south of the Demilitarized Zone and occupied by 6,000 US Marines and South Vietnamese rangers. Land access was cut off when Khe Sanh was besieged by two North Vietnamese divisions with about 20,000 men. The base came to have a greater symbolic importance than its actual strategic value because of the priority accorded to it emphatically and publicly by the White House and MACV.

Air support kept Khe Sanh alive and eventually broke the siege. On an average day, 350 tactical fighters and 60 B-52s pounded the enemy, while airlifters delivered supplies and ammunition, landing under fire when necessary. Each cell of B-52s carpet-bombed a 1.2-mile strip, which created havoc among the besiegers. About 15,000 North Vietnamese and Viet Cong troops were killed, most of them by airpower. “The thing that broke their backs was basically the fire of the B-52s,” Westmoreland said.

The Arc Light sortie rate increased to 1,800 in February 1968 and remained at that level for the rest of the year. In the spring of 1969, B-52s operating under “special security and reporting procedures” bombed North Vietnamese and Viet Cong sanctuaries in Cambodia. Between March 18, 1969 and May 26, 1970, the B-52s flew 4,308 sorties in Cambodia.

Meanwhile, the policy of “Vietnamization” of the war steadily reduced US force levels and activity in Southeast Asia. In September 1970, U Tapao took over as the sole operating base for B-52 sorties. Missions were halted from Andersen and Kadena although Arc Light operations were still directed from the headquarters on Guam.

|

|

In late 1971, intelligence reported a big buildup of North Vietnamese forces just north of the DMZ and an increase of infiltration traffic on the Ho Chi Minh Trail. North Vietnam was preparing for what would be known as the “Easter Invasion” using massed forces. The US plan was to strike the new targets with B-52s before the enemy offensive began.

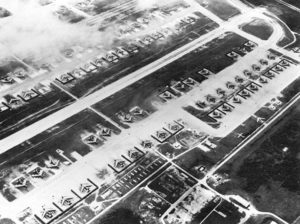

Operation Bullet Shot sent additional B-52s to the theater, raising the total in East Asia to 210, which was more than half of SAC’s entire strategic bomber force. Of these, 155 were based at Andersen, forming the largest concentration of B-52s in history. It took five miles of ramp space to park them. A popular saying claimed that 30 airplanes had to be flying at any one time since there was not room enough for all of them on the base.

The number of support personnel in the 303rd Consolidated Aircraft Maintenance Wing (Provisional) at Andersen, eventually reached 5,000, of which 4,300 were on six-month temporary duty tours. A tent city was thrown up to house the maintenance and support troops. When Arc Light ended in 1973, many of them were on their third consecutive six-month tour to Guam.

The Easter Offensive began March 30 as the North Vietnamese Army crossed the DMZ with 40,000 troops and 400 armored vehicles. US tactical airpower, which by that time had been drawn down to half its peak size, returned and joined B-52s from U Tapao and Andersen in repelling the invasion. Henry A. Kissinger, the national security advisor, argued successfully against using the B-52s in North Vietnam lest they cause a “domestic outcry.” As before, they were employed mostly in the South.

As at Khe Sanh, the massing of ground forces in the face of US airpower proved to be foolhardy, and the invasion was beaten back. However, when the United States suspended air attacks north of the 20th parallel, Hanoi began dragging its feet on peace talks. By early December, “Hanoi had in effect made a strategic decision to prolong the war, abort all negotiations, and at the last moment seek unconditional victory,” Kissinger said. That set the stage for the biggest Arc Light mission of all.

The “Press On” Rules

Operation Linebacker II, which unfolded over the period Dec. 18-29, 1972, launched 729 B-52 sorties in 11 days from Guam and U Tapao against the heartland of North Vietnam, mainly Hanoi and Haiphong. It is often called the “Christmas bombing,” but Christmas was the one day the B-52s did not fly.

The first day saw attacks by 129 B-52s, the biggest bomber attack force assembled since World War II. Of these, 87 were from Andersen; it took an hour and 43 minutes for them to taxi out and take off. The choreography of the massive launch—dubbed the “Elephant Walk”—was handled by “Charlie Tower,” located between the approach ends of the runway and manned by experienced old hands who solved problems as they arose.

Since November, the B-52s had been operating under “Press On” rules, which meant that missions into North Vietnam would continue despite aircraft malfunctions or MiG threats. For Linebacker II, the Press On rules were tougher. “The loss of two engines en route or complete loss of the bombing computers, radar system, defensive gunnery, or ECM [electronic countermeasures] were not legitimate grounds for abort,” said Brig. Gen. James R. McCarthy, who as a colonel in 1972 had commanded one of the two B-52 wings at Andersen. Ground crews sometimes stayed aboard the aircraft and continued maintenance on the way to North Vietnam.

Spare aircraft were preflighted and made ready. If necessary, a crew could transfer to the spare bomber, taking their mission materials and equipment with them. The exercise was known as a “bag drag.”

Linebacker II is associated in popular memory almost exclusively with the B-52s. In fact, other aircraft flew almost half the Air Force sorties, which included combat air patrol, suppression of SAMs, electronic countermeasures, and various support missions. Nevertheless, the B-52s were clearly the power hitters and delivered the main message to the North Vietnamese.

They approached from the northwest, along the Red River Valley and Thud Ridge, and on the first night struck airfields and rail yards around Hanoi. Ninety-four percent of the attacking bombers put their ordnance on target.

The most serious trouble came on the third night, when six B-52s—of 99 launched—were shot down by SA-2 missiles. There was considerable opinion that the fault lay with tactics decided and directed by SAC headquarters, half a world away in Omaha. The bombers were repeatedly sent on the same approach routes, at the same altitudes, and at the same times of day.

A particularly questionable part of the order forbade maneuvering to evade SAMs or MiGs. There were two reasons given for this: concern about midair collisions among bombers or with other aircraft, and more important, the reduced risk of hitting civilian areas if the bombers stayed on planned course and in trail formation. In addition, a “post-target turn,” a steep, 45-degree banked turn immediately after release of bombs, was directed. This was a standard SAC maneuver to help bombers get away from nuclear blast, which was not one of the threats they encountered over Hanoi.

“The inbound heading to the target and the post-target turn remained relatively unchanged for the first three days of Linebacker II,” McCarthy said after the war. “This, in my opinion, caused the high B-52 losses sustained on the second and third days.” After that, the rules changed. SAC delegated authority to select axes of attack and withdrawal routes to 8th Air Force on Guam. A smaller post-target turn was adopted. The B-52s could maneuver in self-defense. There were further losses—15 in all for the 11-day operation—but never again more than two a night.

Final Mission: Cambodia

Linebacker II struck railroad yards, storage facilities, radio communications facilities, power plants and transformers, airfields, SAM sites, and bridges. North Vietnam lost 80 percent of its power production and its military infrastructure was severely battered. It was obvious that the B-52s could have wiped Hanoi and Haiphong off the map had that been their purpose. Instead, damage to civilian areas was limited.

The North Vietnamese understood that there would be more to come if they continued to slow roll the peace talks. Besides, they were running out of SAMs and they knew from the Russian trawler at Pati Point that they had made only a small dent in the B-52 force. They returned to the peace talks and a cease-fire was signed in Paris on Jan. 27, 1973. Kissinger, who had been reluctant to use the B-52s in the north, acknowledged that it had “speeded the end of the war” and most likely was “the only measure that would have done so.”

B-52 missions in Vietnam stopped with the peace agreement, but Arc Light operations continued for a while in other parts of Southeast Asia. The final mission was in Cambodia on Aug. 15, 1973.

During the eight years and two months of Arc Light, the full power of the B-52s was seen only sporadically. The exceptions were employment against a massed enemy, as at Khe Sanh, and in the strategic operation of Linebacker II. The United States had already made its critical mistake in strategy before B-52s flew the first Arc Light mission. In April 1965, the air campaign against North Vietnam had been downgraded to a supporting action for the ground war in the South although the war was instigated, perpetuated, and sustained by the North. That barrier made victory impossible, but South Vietnam might have survived as a nation if Arc Light had continued.

“There seems to be no question that the B-52 bombing of Hanoi and the terrific casualties North Vietnamese military forces suffered from US air attacks in 1972 intimidated the North Vietnamese leadership,” said Marshall L. Michel III in The 11 Days of Christmas. “Had Nixon remained in power and the United States kept a significant B-52 presence in Asia, it is at least questionable if the North Vietnamese would have again risked a conventional invasion of South Vietnam. It was only after the fall of Nixon that the fall of South Vietnam became inevitable.”