There was never any chance that Japan would win World War II in the Pacific. When Japan attacked the US at Pearl Harbor, it bit off more than it could chew. Japan reached the limits of its territorial expansion in the next few months, and, from then on, it was a steady rollback as Japanese forces were ousted from the Solomons, New Guinea, the Marianas, the Philippines, Iwo Jima, and Okinawa.

After Germany surrendered in May 1945, the full war effort was focused on the Pacific. It was nominally an Allied effort, but almost all of the forces closing in on Japan were American. The Japanese Navy was gutted. What remained of Japanese airpower was mostly kamikaze aircraft, although there were thousands of them and plenty of pilots ready to fly on suicide missions. Nevertheless, Japan hung on with great tenacity. It still had 4,965,000 regular army troops and more in the paramilitary reserves.

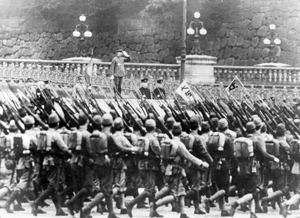

|

Emperor Hirohito reviews Japanese troops in Tokyo in June 1941. Only when Japan suffered severe hardship did his enthusiasm for the war begin to wane. |

The outcome of the war was sealed in 1944 when the United States obtained air bases in the Marianas. From there, B-29 bombers could reach Tokyo and all important targets in Japan. Night after night, the B-29s rained firebombs and high explosives on the wood and paper structures of Japan. On March 9, 1945, the bombers destroyed 16 square miles of Tokyo and killed 83,793 Japanese.

Gen. Henry H. “Hap” Arnold, commander of the Army Air Forces, predicted that the bombing would be sufficient to prevail and “enable our infantrymen to walk ashore on Japan with their rifles slung.” Adm. Ernest J. King, Chief of Naval Operations, believed that encirclement, blockade, and bombardment would eventually compel the Japanese to surrender.

Others, notably Gen. George C. Marshall, the influential Army Chief of Staff, were convinced an invasion would be necessary. In the summer of 1945, the United States pursued a mixed strategy: continuation of the bombing and blockading, while preparing for an invasion.

Japan had concentrated its strength for a decisive defense of the homeland. In June, Tokyo’s leaders decided upon a fight to the finish, committing themselves to extinction before surrender. As late as August, Japanese troops by the tens of thousands were pouring into defensive positions on Kyushu and Honshu.

Old men, women, and children were trained with hand grenades, swords, and bamboo spears and were ready to strap explosives to their bodies and throw themselves under advancing tanks.

An invasion would almost certainly have happened had it not been for the successful test of the atomic bomb in the New Mexico desert on July 16, an event that gave the United States a new strategic option.

The overall invasion plan was code-named Operation Downfall. In April 1945, the Joint Chiefs of Staff named Gen. Douglas MacArthur commander in chief of US Army forces in the Pacific in addition to his previous authority as commander in the South Pacific. He would lead the final assault on Japan.

The invasion plan called for a US force of 2.5 million. Instead of being demobilized and going home, soldiers and airmen in Europe would redeploy to the Pacific. Forces already in the Pacific would be joined by 15 Army divisions and 63 air groups from the European Theater.

Operation Downfall consisted of two parts:

Operation Olympic. This invasion of Kyushu, the southernmost of Japan’s main islands, was set for Nov. 1, 1945. It would be an amphibious landing a third larger than D-Day in Normandy. The expectation was that nine US divisions would be opposed by three Japanese divisions. (In fact, Japan had 14 divisions on Kyushu.) Far East Air Forces would support the invasion with 10 fighter groups, six heavy bomb groups, four medium bomb groups, four light bomb groups, three reconnaissance groups, and three night fighter squadrons. In addition, the B-29s would continue their strategic bombardment. MacArthur said the southern Kyushu landings would be conducted “under cover of one of the heaviest neutralization bombardments by naval and air forces ever carried out in the Pacific.”

Operation Coronet. This was the code name for an invasion, in March 1946, of Honshu, the largest of the Japanese islands. Coronet would require 1,171,646 US troops, including a landing force of 575,000 soldiers and marines. It would be the largest invasion force ever assembled. Operation Coronet would make use of airfields on Kyushu captured during Operation Olympic.

As Japan’s desperation grew, the ferocity of its armed resistance intensified. The code of bushido—“the way of the warrior”—was deeply ingrained, both in the armed forces and in the nation. Surrender was dishonorable. Defeated soldiers preferred suicide to life in disgrace. Those who surrendered were not deemed worthy of regard or respect. On Kwajalein atoll, the fatality rate for the Japanese force was 98.4 percent. On Saipan, nearly 30,000—97 percent of the garrison—fought to the death. On Okinawa, more than 92,000 Japanese soldiers in a force of 115,000 were killed.

Japan continued the fight with fanatical determination in the belief that the willingness of soldiers and sailors to sacrifice their lives would compensate for shortfalls in military capability. The Ketsu-Go (“Decisive Operation”) defense plan for the homeland counted on civilians, including schoolchildren, taking part in the battle.

|

Gen. Douglas MacArthur, commander of Allied forces in the Southwest Pacific, wades ashore at the island of Leyte, Philippines. |

An Elusive Answer

Some 17 million persons had died at the hands of the Japanese empire between 1931 and 1945, and more would be certain to die during the final stand.

Japan had been controlled by the military since the 1930s. In 1945, power was vested in the “Big Six,” the Supreme Council for the Direction of the War. Members were the prime minister, foreign minister, Army minister (also called War Minister), Navy minister, chief of naval general staff, and chief of the Army general staff. Army and Navy ministers were drawn from the ranks of serving officers. The dominant member of the Big Six was the War Minister, Gen. Korechika Anami.

Emperor Hirohito, regarded as divine and revered as the embodiment of the Japanese state, was supposedly above politics and government. In fact, he was interested in, and well-informed about, both of them. His enthusiasm for the war did not wane until the bombs and hardship reached Japan.

On March 18, Hirohito toured the areas of Tokyo firebombed March 9 and 10; he concluded that the war was lost and that Japan should seek an end to it as soon as possible. However, Hirohito agreed with the strategy of waiting to negotiate until Japan won a big battle, strengthening its bargaining position.

The prime minister was Kantaro Suzuki, a retired admiral, who sometimes sided with the council’s peace faction but aligned frequently with the military hardliners, who dominated meetings and policy.

Japan still held most of the territory it had captured in Asia and Indochina, and hoped to keep some of it. Its remaining military strength was considerable. If it could inflict painful casualties on the United States, Japan might be able to secure favorable terms, it thought.

Today, a fierce argument still rages about what the casualty toll might have been if the Operation Downfall invasion had taken place. The answer is elusive. Wartime casualty estimates were based on inaccurate assumptions—usually low—about enemy strength. Postwar analysis has been severely distorted by academicians and activists on the American left seeking to prove that neither an invasion of Japan nor the atomic bomb was necessary to end the war.

After the war, President Truman said that Marshall told him at Potsdam (July 1945) that the invasion would cost “at a minimum one-quarter of a million casualties, and might cost as [many] as a million, on the American side alone.” For this, Truman was ridiculed. There is no independent evidence of what Marshall said at Potsdam. Truman may have been embellishing it, but his numbers were not preposterous, as is often alleged.

In fact, Joint Staff planners on two occasions worked up casualty estimates and came out in the same range. In August 1944, using casualty rates from fighting on Saipan as a basis, they said that “it might cost us a half-million American lives and many times that number in wounded” to take the Japanese home islands. An April 1945 report projected casualties of 1,202,005—including 314,619 killed and missing—in Operations Olympic and Coronet, and more if either of the campaigns lasted more than 90 days.

MacArthur’s staff made several estimates for Operation Olympic, one for 125,000 casualties in the first 120 days and another for 105,000 casualties in the first 90 days. Marshall sent MacArthur a strong hint about Truman’s concern about casualties, whereupon MacArthur, who wanted the invasion to go forward, backed away from the estimates, declaring them too high.

At a critical White House meeting on June 18, Marshall gave his opinion that casualties for the first 30 days on Kyushu would not exceed the 31,000 sustained in a similar period of the battle for Luzon in the Philippines. (Marshall took that number from an inaccurate report. Casualties for the first 30 days on Luzon had been 37,900.) Others at the meeting based their estimates on Okinawa, where US casualties were about 50,000.

|

Gen. Korechika Anami, Japan’s War Minister, opposed the surrender but would not go against the Emperor. |

(To put these numbers in some perspective, the losses for the Normandy invasion, from D-Day through the first 48 days of combat in Europe, were 63,360.)

Neither comparison was apt. The Japanese forces on Luzon and Okinawa were a fraction of the size of the force waiting in the home islands. As Marshall and other military leaders were about to learn, they had drastically underestimated the strength of the Japanese defenses on Kyushu and Honshu.

US intelligence agencies had long since broken Japan’s secret codes. “Magic” was the name given to intelligence from intercepted diplomatic communications, and “Ultra” was intelligence from Japanese Army and Navy messages. From these intercepts, it was known that Japan intended to fight to the end.

On June 15, an intelligence estimate had reported six combat divisions and two depot divisions, a total of about 350,000 men, on Kyushu. However, beginning in July, Ultra intercepts revealed a much larger force, with new divisions moving into place.

Subsequent reports raised the estimated number of troops, first to 534,000 and then to 625,000. That nearly doubled the June estimate, but it was still too low. In actuality, Japan had 14 combat divisions with 900,000 troops on Kyushu, concentrated in the southern part of the island around the Olympic landing beaches. The American force committed to Kyushu was 680,000, of which 380,000 were combat troops. Japanese forces were being pulled back into Honshu as well. Between January and July, military strength in the home islands doubled, from 980,000 to 1,865,000.

The Bombs Fall

Would the United States have pressed ahead with Operation Downfall anyway? If so, casualties would be much higher than predicted. If not, Tokyo would have won its bet that the United States would back down if the price in American lives could be made high enough.

It did not come to the test. The casualty estimates were never updated to take the Ultra intercepts into account. On Aug. 4, the war plans committee of the Joint Chiefs of Staff suggested reviewing the plan in view of the Japanese buildup, but by then the decision had been made to drop the atomic bomb.

The first atomic bomb fell on Hiroshima on Aug. 6. Japanese officials understood what it was; Japan had itself been working on a fission bomb. The Big Six shrugged off the loss and held their position.

When the second atomic bomb was dropped on Nagasaki Aug. 9, the Navy chief, Adm. Soemu Toyoda, argued that the US could not have much radioactive material left for more atomic bombs. The hardliners refused to consider surrendering unless the Allies agreed that Japanese forces could disarm themselves, that there would be no prosecution for war crimes, and that there would be no Allied occupation of Japan.

War Minister Anami said the military could commit 2,350,000 troops to continue the fight. In addition, commanders could call on four million civil servants for military duty.

The Soviet Union declared war on Japan Aug. 8, which put pressure on the Big Six from a different direction. The Japanese had hoped, without sound reasons or encouragement, that they could cut a deal with the Soviets to counterbalance the Americans and permit the Japanese to keep some of their conquered territory.

On Aug. 10, the Foreign Ministry, acting on approval of the Emperor, sent notice to the US and the Allies that Japan could accept the demand for surrender if “prerogatives” of the Emperor were not compromised. The United States replied that the authority of the Emperor would be subject to the Supreme Commander of Allied Powers. The hardliners dug in, and the peace faction fell into disarray. Vice Adm. Takijiro Onishi, vice chief of the naval general staff, declared: “If we are prepared to sacrifice 20 million Japanese lives in a special attack [kamikaze] effort, victory will be ours.”

As the world watched and waited, Gen. Carl A. Spaatz, commanding US Strategic Air Forces in the Pacific, redirected the B-29 force away from the firebombing of cities to precision attack of military targets, especially transportation. Marshall and his staff were studying an alternate strategy, to use atomic bombs in direct support of invasion. The United States expected to have at least seven bombs by Oct. 31. They were told by Manhattan Project scientists that lethal radiological effects from an atomic bomb would reach out 3,500 feet but that the ground would be safe to walk on in an hour.

The impasse was broken by the Emperor who decided to surrender and announce his decision to the Japanese people in the form of an “Imperial Rescript” broadcast on the radio.

Army and Navy officers put up violent resistance. Some attempted to destroy the recorded rescript before broadcast. The commander of the Imperial Guard, who would not go along with the plot, was assassinated by Army hotheads. They tried to find and kill Suzuki as well. They attempted to persuade Anami—who was opposed to the surrender but would not oppose the Emperor—to join in a coup. Had he done so, the surrender might have failed, but Anami committed suicide instead.

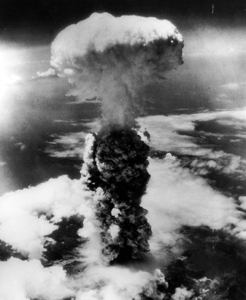

|

A mushroom cloud rises over the Japanese city of Nagasaki on Aug. 9, 1945, three days after the first atomic bomb struck Hiroshima. |

Enter the Revisionists

The Emperor’s rescript was broadcast at noon on Aug. 15, and the war was over.

There was some criticism of the use of the atomic bomb in the immediate postwar period, but it was in the 1960s that the “revisionist” school of historians emerged, aggressively critical of the United States and challenging the necessity and motive for using the atomic bomb.

The central revisionist claim is that the atomic bombs were not necessary and that, even without them, the war soon would have been over. Japan was on the verge of surrender. The United States prolonged the war by insisting on unconditional surrender and dropped the atomic bombs mainly to impress and intimidate the Russians. In any case, the casualty estimates for an invasion of Japan were exaggerated.

The latest in the revisionist repertory is Racing the Enemy: Stalin, Truman, and the Surrender of Japan (2005) by Tsuyoshi Hasegawa, professor of history at University of California, Santa Barbara. “Americans still cling to the myth that the atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki provided the knockout punch,” Hasegawa said. “The myth serves to justify Truman’s decision and ease the collective American conscience.”

A regular part of the revisionist litany is recitation of wartime opinions of Army Air Forces leaders, including Arnold and Gen. Curtis E. LeMay, who thought the war could have been brought to an end by conventional bombing. They ignore LeMay’s later assessment that “the atomic bomb probably saved three million Japanese and perhaps a million American casualties.”

Revisionists like to cite the US Strategic Bombing Survey of 1946, which said the Japanese would probably have surrendered by Nov. 1, even if Russia had not entered the war and even if no invasion was planned. The survey is not nearly as authoritative a product as the title sounds and its conclusions are contrary to the overwhelming weight of evidence.

It is reasonable to consider several factors as contributing to the surrender—bombing and blockade, Soviet entry into war, the impending invasion—but the Emperor’s decision was key.

When Hirohito told his advisors that he intended to surrender, he gave three reasons: bombing and blockade, inadequate provisions to resist invasion, and the atomic bombs. He said on Aug. 14 that “a peaceful end to the war is preferable to seeing Japan annihilated.”

In the Imperial Rescript of Surrender, he said, “The enemy has begun to employ a new and most cruel bomb, the power of which to do damage is, indeed, incalculable, taking the toll of many innocent lives.” Hirohito, at a meeting with Mac-Arthur Sept. 27, 1945 said, “The peace party did not prevail until the bombing of Hiroshima created a situation which could be dramatized.”

Japan was not ready to surrender prior to the dropping of the atomic bombs. Without them, the war would have gone on. Those who think otherwise seriously underestimate Japan’s residual strength and determination.

Bombing and blockade would have eventually ended the war at some point but were not likely to have done so anytime soon. The B-29 firebombing would probably have resumed, and two nights of it on a par with March 9 would have exceeded the death toll of both atomic bombs.

Operation Olympic would most likely have gone forward against a Japanese force with 600,000 more troops than previously estimated on Kyushu—and that would have left the invasion of Honshu and Operation Coronet yet to come.

In the end, Japan would have been defeated, but the price in lives on both sides would have been terrible.

John T. Correll was editor in chief of Air Force Magazine for 18 years and is now a contributing editor. His most recent article, “Doolittle’s Raid,” appeared in the April issue.