Even for heroes, heroism is usually a one-time event, but Duane D. Hackney made a habit of it. He was the most decorated airman in the Air Force. Eight rows of ribbons stretched from the top of his pocket up to his collar. Many of them were for individual acts of valor, earned during 200 combat missions in Vietnam. They included the Air Force Cross, the Silver Star, the Distinguished Flying Cross with three oak leaf clusters, the Airman’s Medal, and the Air Medal with 18 oak leaf clusters. In later years, Hackney favored long-sleeved uniform shirts, which covered some of the burn scars on his arms.

|

Air Force pararescue jumper Duane Hackney on duty in Southeast Asia, checking the jungle penetrator on his HH-3 helicopter. |

Hackney was born in Flint, Mich., in June 1947. He lettered in football, baseball, and swimming at Beecher High School and joined the Air Force in June 1965. Qualifying as a pararescue jumper, or PJ, took about a year. It included medical and scuba training, combat survival school, jump school at Ft. Benning, Ga., Army Ranger school, topped off by “goat lab” at Eglin AFB, Fla.

He was smaller than some in his PJ class, but Hackney was stronger than he looked. At Ft. Benning, a contingent of Navy SEALs lost money betting that their champion could outlast Hackney in one-handed push-ups. He was the honor graduate of his group and got his choice of assignments. He chose Vietnam. “The top graduates got lucky and could pick Vietnam,” he said. “Others got stuck with Bermuda or England. We all knew where the action was.”

He began his first combat tour Sept. 27, 1966, at Da Nang, the northernmost US air base in Vietnam, 85 miles south of the Demilitarized Zone. Da Nang was already known as “Rocket City” because of the frequent Viet Cong and North Vietnamese mortar and rocket attacks.

It was also home to the 37th Aerospace Rescue and Recovery Squadron whose mission was to go get pilots who had been shot down or other troops stranded behind enemy lines. The conspicuous stars of ARRS were the PJs, who went down on jungle penetrators, often under fire, to bring out the wounded. The squadron flew the HH-3E, most famous of the rescue helicopters and called the “Jolly Green Giant” because of its green and brown camouflage. The rescue helicopters flew in pairs. The “low bird” picked up the survivor. The “high bird” waited nearby, ready to help if needed, or to extract the low bird crew if they were shot down themselves.

|

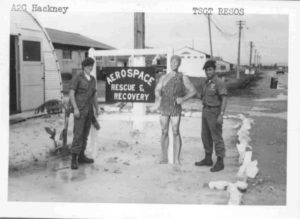

Hackney (l) and TSgt. Phil Resos, snapped with their mascot, the Jolly Green Giant. |

Into the Fray

Hackney was an airman second class, as the two-stripe E-3 grade was then called. He flew his first rescue mission within a week of arriving in Vietnam. On Oct. 2, he was the PJ on Jolly Green 36, an HH-3E that recovered a fighter pilot on the ground eight miles southeast of Sam Neua in Laos.

It was a surge time for traffic on the Ho Chi Minh Trail, the infiltration route that ran down the western side of the Annam Mountains, through the Laotian panhandle into South Vietnam and Cambodia. Access to the trail from North Vietnam was through several mountain passes, the main one being the Mu Gia Pass, about 75 miles above the DMZ. It was there that Hackney flew his most famous mission on Feb. 6, 1967.

Early that morning, Capt. Lucius L. Heiskell, a forward air controller from Nakhon Phanom, Thailand, flying low and slow in a Cessna O-1 Bird Dog, was shot down just north of Mu Gia. He parachuted into a small valley several miles to the east, an area of rugged karst and thick jungle growth. Heiskell made contact on his survival radio with circling aircraft but signed off after a few minutes because he heard enemy search parties approaching.

Two Jolly Green rescue helicopters scrambled from Nakhon Phanom, just across the Laotian panhandle from Mu Gia, at 10:05 a.m., and reached the pass half an hour later. The high bird, Jolly Green 36, remained on orbit, while Maj. Patrick H. Wood threaded the low bird, Jolly Green 05, along the valley, avoiding 37 mm guns firing from the north ridge. Wood hovered above Heiskell’s last known position and sent down his PJ. That was Hackney, who was on temporary duty at NKP. He climbed on the penetrator and descended through three levels of jungle growth. On the ground, he saw footprints but could not find Heiskell, so the helicopters returned to NKP to await further developments.

Heroism Runs in the Family

At 4:30 that afternoon, a fighter pilot at Mu Gia picked up a radio message from Heiskell. The two Jolly Greens launched again and got there an hour-and-a-half before dark. Two A-1H “Sandy” attack aircraft were at the scene and in radio contact with Heiskell. However, the mountaintops were hidden by overcast, so the Sandys could not fly into the valley to provide protection for the helicopter. The entire crew of Jolly Green 05 wanted to try the rescue anyway, and Wood decided to go in without escort. The helicopter crew raised Heiskell on the radio. He had some abrasions and minor injuries but was able to direct the Jolly Green to his location. Hackney went down for him and three minutes later, Wood reported that Heiskell was aboard.

Back at NKP, Heiskell’s fellow FACs gathered around the radio at squadron operations, cheering as they followed the news. The jubilation did not last long. Jolly Green 05 pulled out under heavy ground fire and almost immediately radioed that “we’ve been hit, we’ve been hit!” A burst of 37 mm flak had torn into the helicopter amidship, causing severe damage and setting off a raging fire.

|

Hackney (l) and a fellow PJ, Sgt. William Flower, in a photo from the early 1970s. |

“I was bending over him [Heiskell] doing a medical evaluation when flak hit us,” Hackney said. “There was smoke and flames everywhere. The survivor reached out for help. I kept my emergency parachute hanging on the forward bulkhead near the left scanner’s window. I grabbed it and helped the survivor put it on. I left the survivor by the crew entrance door and headed aft to find another parachute. I found one hanging by the ramp and began to put it on. That’s when the second burst of flak hit us. There was an explosion and I was thrown backwards—hard. I felt a sharp pain in my left arm. I tried to get my balance and was surprised to see my helicopter flying away from me. I had been blown out the aft ramp of the HH-3. I did not have the parachute completely on yet, and was only a couple of hundred feet above the treetops.”

He pulled the ripcord and held tight to the parachute harness. The parachute was still opening when he hit the trees, but it slowed his fall and left him suspended several feet above the ground. He freed himself and climbed down. The helicopter, out of control, crashed into a karst outcropping at high speed. The high bird dropped down to pick up Hackney, but found no trace of Heiskell or the other members of the Jolly Green 05 crew.

Hackney was in shock and badly burned, and when the helicopter landed at NKP, he was exhausted and went “out like a light” on the hospital stretcher. He awoke when he heard a medical technician say he thought Hackney was dead. “That really scared me,” he said.

He would later receive the Air Force Cross for his actions that day. “With complete disregard for his own safety, Airman Hackney fitted his parachute to the rescued man,” the citation said. “In this moment of impending disaster, Airman Hackney chose to place his responsibility to the survivor above his own life.”

“Heroism seems to have run in Duane’s immediate family,” said Robert L. LaPointe, a former PJ, author of PJs in Vietnam, and keeper of the USAF Pararescue Association historical archive. “His father won the Silver Star and Purple Heart in World War II. He had kicked a Japanese grenade out of a foxhole and jumped on three soldiers to protect them from the blast. Duane said, ‘My father told me to keep my head down in Vietnam. While I was [there] in the hospital, I got a letter from dad. He wrote, I told you to keep your head down.’”

Hackney was back in action before the end of the month and took part in another extraordinary mission several weeks later. On March 13, two marine troop transport helicopters went down just south of the DMZ, and Hackney was a PJ on one of the HH-3Es sent to get the survivors. The crash site was on the slope of a mountain ridge in jungle so thick that the rescue hoist cable had to be fully extended 240 feet to reach the ground. As Hackney rode up from his last descent, “bullets began to pepper the aircraft like popcorn popping,” the pilot’s mission report said.

As Hackney worked on the wounded in the helicopter cabin, a bullet grazed his helmet and knocked him out. He regained consciousness shortly and resumed setting fractures and applying tourniquets. His own injuries would have been worse, but the emergency radio in his pocket had stopped a piece of shrapnel. Both he and the marine wounded were treated at the field hospital at Dong Ha.

A Star Turn

His Air Force Cross was presented in September and, at the same ceremony, he received the Silver Star for bravery during a rocket attack on Da Nang July 15. “Airman Hackney entered the most heavily damaged area while the attack was occurring and was personally responsible for saving the lives of six men,” the citation said. Hackney “unhesitantly approached burning aircraft and exploding ordnance to rescue wounded personnel.”

His combat tour ended in October 1967, and he was assigned to the 41st Aerospace Rescue and Recovery Squadron at Hamilton AFB, Calif. He made the rounds of network television programs interested in his story. He appeared on “The Tonight Show” with Johnny Carson, and on the Ed Sullivan, Art Linkletter, and Joey Bishop shows, and spent Christmas 1967 in Monaco as the guest of Prince Rainier and Princess Grace.

Detroit, in his home state of Michigan, put on “Hackney Day,” at which he was guest of honor. He was Military Airlift Command Airman of the Year in 1967 and in 1968, he received the Cheney Award, named for an airman killed in Italy in World War I and given for “an act of valor, extreme fortitude, or self-sacrifice.”

Hackney returned to Vietnam for a second combat tour in 1970. His name shows up regularly on reports of air rescue missions in North and South Vietnam and Laos. One of the more eventful of these was a foray into Laos April 9, 1971, to bring out four South Vietnamese soldiers who were encircled by the enemy. Three HH-53Cs—larger than the HH-3 and with more range—responded to the call. Hackney, by then a staff sergeant, was one of three PJs on Jolly Green 70.

Heavy ground fire stopped the first attempt to lower the jungle penetrator, and the lead PJ, A1C Ervin A. Petty, took out a .51-caliber gun site with the helicopter’s left window minigun. The South Vietnamese were on the slope of a hill, and Hackney suggested a low hover and pulling them straight into the door rather than using the hoist. Petty straddled Hackney in the door, and Hackney pulled the soldiers high enough for Petty to get them the rest of the way inside.

The exchange of fire was withering. An A-1H Sandy was shot down. The three miniguns on Jolly 70 were spitting out 6,000 rounds a minute, and the helicopter had been hit in No. 1 engine and other critical areas. PJ A1C Donald J. Pecoraro saw Petty and Hackney go down. Hackney’s helmet had been hit, but he appeared to have only a flesh wound, along with loss of balance and difficulty standing and walking. Petty’s wound was worse. He was hit by a .51-caliber round that ripped away the back of his right bicep.

Petty’s fellow PJs insisted that he be taken to the Army hospital at Da Nang. They had been there for medical proficiency training and believed the doctors less quick to amputate than at some facilities. Petty survived—and kept his arm. Meanwhile, the medics noticed a bullet hole in Hackney’s helmet and feared trouble. Incredibly, though, the bullet had gone in at the front, looped across the top of his skull inside the helmet, and exited at the back.

“He did not want a Purple Heart,” said James Scott, a PJ who roomed with Hackney for a while at Da Nang. “He did not want any recognition. He just wanted to pull his share and do his job.”

In 1973, Hackney was a tech sergeant with a line number for promotion to master sergeant, but he decided to leave the Air Force. For the next four years, he was a deputy in the Genesee County Sheriff’s Department in his hometown of Flint. In 1977, he returned to the Air Force, even though he had to take a cut in grade. “The main reason I came back to the Air Force was because I missed the traveling and camaraderie,” he told Airman Magazine. “When I had an opportunity to get back in uniform as an E-4, I jumped at it.”

A Sadly Short Retirement

He moved back through the ranks quickly, making staff sergeant and tech sergeant at his first eligibility. He went through rescue training again and became a PJ instructor. He also served with special operations forces in Turkey and Grenada.

While stationed in England in 1980, he took part in the rescue of two British civilians who had been mountain climbing in Wales. He sustained several injuries, including a broken hip and a fractured skull, during that operation. In 1981, he had a heart attack in England and that was the end of his days as a PJ.

Back from England, Hackney was assigned to the 23rd Air Force intelligence division at Scott AFB, Ill. It was there that he met Carole Matlack one day at the soda machine. She was a senior airman at the Military Airlift Command Rescue Communications and Control Center, and she had never heard of Duane Hackney. When he was first at Da Nang, she said, “I was five years old and did not really follow the news of Vietnam.” They were married in 1982.

He did not talk about Vietnam, and it was from studying Air Force history for her promotion test that she learned of what her husband had done. Their son, Jason, was born in 1984.

Hackney did not like the intelligence work. He cross-trained into the security police field and, in 1985, moved to K. I. Sawyer AFB, Mich., a Strategic Air Command base, where he was first sergeant of the security police squadron. He found the responsibility of working with 450 airmen satisfying. Hackney was First Sergeant of the Year in 8th Air Force in 1987, and was a chief master sergeant when he retired in July 1991.

The Hackneys built a new home in Trout Run, Pa., and moved there in November 1992. He attended Lycoming College in nearby Williamsport, planning to become a nurse anesthetist.

Hackney had completed one full semester and was in his second semester when he had another heart attack and died in September 1993. He was 46. Visitors packed the funeral home in Flint for three straight days to pay their respects. The Flint Journal reported that the funeral procession was five miles long.

He is not forgotten. In 2006, the Air Force Basic Military Training Center at Lackland AFB, Tex., dedicated buildings to nine enlisted heroes. One of them was named for Duane Hackney. In 2009, he was inducted into the Michigan Aviation Hall of Fame.

“When I arrived in Vietnam in 1971, Duane and others had set high standards for us to follow,” says LaPointe of the USAF Pararescue Association. “When one reads the facts concerning Duane’s actions on the day he earned the Air Force Cross, many would call his survival miraculous. Some claimed it was instinctive, the result of intensive training. Regardless of how Duane survived, he became an Air Force legend. Being a legend after the Vietnam War was not an easy task. When asked about his Air Force Cross, Duane often stated, ‘I was just doing my job. Any one else in my situation would have done the same.’”

“Duane lived life to the very limit,” says Carole Hackney Bergstrom, who now lives in Williamsport. “It seemed to me that he lived every single day as if it might be his last. Every single day he did as much as he could jam into one day. … He never did anything halfway. It was all or nothing. … There is no doubt in my mind that this all or nothing attitude is what got Duane through Vietnam.”