On one August day last year, some US ground troops were preparing to move out down a certain dangerous road in Afghanistan. SrA. Andres Morales of the Air Force had a related mission. As it happened, his mission grew and grew.

At first, Morales was tasked to supply intelligence information about three specific points of interest along that Afghan road route. Morales, an analyst in DGS-2, USAF’s Distributed Common Ground System (DCGS) node at Beale AFB, Calif., provided the information within minutes. It was based on a blend of imagery and electronic communications signals captured by the sensors on surveillance and reconnaissance aircraft flying near the route.

Then came the unplanned items. Morales learned about expanded needs of the troops on this convoy mission. He continued to offer support. Over the course of seven hours, he kept these soldiers supplied with updated intelligence. All the while, he stayed in close contact with them, using a secure chat room on the US military’s classified network.

|

SrA. Julia Richardson analyzes computer imagery on the new operations floor of Distributed Ground System-1 at Langley AFB, Va. (USAF photo by SrA. Dana Hill) |

Morales’ analysis identified eight areas of suspicious activity along the route, one of which turned out to be an improvised explosive device that might have wounded or killed some of these soldiers had it gone undetected. The soldiers also confiscated three insurgent weapons caches nearby, located as a result of the airman’s involvement.

The Air Force today doesn’t often disclose the details of its intelligence-surveillance-reconnaissance (ISR) activities in Afghanistan and Iraq or elsewhere around the globe. Yet service officials say this declassified account of Morales’ mission is by no means unique in its scope and outcome.

“We literally have thousands of airmen now who operate this weapon system [DCGS] and are in direct contact with the forces forward,” said Maj. Gen. Bradley A. Heithold, commander of the Air Force Intelligence, Surveillance, and Reconnaissance Agency (AFISRA) at Lackland AFB, Tex., in an interview.

Five years ago, however, this type of support was not the norm. While DCGS existed then, this sophisticated intelligence fusion system was organized very differently across the Air Force. The system prevented USAF officials from fully exploiting the synergy of its distributed global analytic hubs.

Simply put, it was not possible for an airman at Beale to provide the same type of actionable intelligence to troops at the forward edge of operations, as Morales did.

Skilled in the Arts

Air Force leaders saw these limitations. More broadly, they recognized that the nature of warfare had inexorably shifted; intelligence and operations could no longer be viewed as separate entities, and quickly finding and identifying targets loomed as the US military’s biggest challenge. The Air Force in 2006 launched an ambitious overhaul of its ISR enterprise.

The service leadership created a new Air Staff directorate for ISR, and other organizations were revamped to streamline authorities and optimize how ISR echelons present themselves to Air Force and joint force commanders as well as the national intelligence community.

Strong emphasis was placed on creating a cadre of senior officers and enlisted airmen skilled in the arts of this realm. A new foundation of the trade was built on new strategies and far-reaching documents stating how the service would pursue future ISR systems, including remotely piloted aircraft.

All this happened against the backdrop of the Air Force pushing more ISR assets—in particular the MQ-1 Predator and MQ-9 Reaper remotely piloted aircraft—into the war theater at an accelerated pace to meet the insatiable demand for the overwatch that they provide.

Fast forward to today. These actions have borne fruit.

|

An MQ-9 Reaper remotely piloted aircraft comes in for landing at an airfield in Afghanistan. (USAF photo by SSgt. Brian Ferguson) |

“I think the changes have been quite profound,” said James R. Clapper Jr., undersecretary of defense for intelligence, in an interview. Their impact, he continued, “is a reflection of the fact that ISR kind of drives everything else. It drives operations.”

DCGS has been freed from its organizational restraints, and is now a no-kidding globally networked system able to swiftly and easily draw upon the expertise of analysts from any one of its distributed worldwide sites.

Clapper characterized this capability as the US military’s “central nervous system” for processing, exploiting, and disseminating imagery and signals intelligence products. The ability of DCGS to link with intelligence centers in the war theater “has been tremendous,” he said.

Success is evident on other ISR fronts, too. After a drought of several years, the Air Force now has a career intelligence officer serving as the head of the ISR directorate in a combatant command. In this case, it is Brig. Gen. VeraLinn Jamieson, the J-2 at US Southern Command. And the way has been cleared for an Air Force general officer to serve as J-2 of US Strategic Command.

The number of Air Force RPAs supporting operators in the war theater has ballooned from one continuous MQ-1 air patrol in the early days of the war in Afghanistan in 2001 to more than 40 around-the-clock orbits of MQ-1s and MQ-9s today. Plans call for the Air Force to have 65 orbits in place in 2013.

The service needed only about 10 months to take the MC-12W ISR Liberty Project Aircraft all the way from concept to fielding in Southwest Asia, a feat Clapper described as “a superb achievement” on a timeline “virtually unheard of.” These aircraft provide invaluable full-motion video and electronic eavesdropping support to troops in Afghanistan and Iraq.

Back when the service launched the makeover, USAF’s stated goal was this: “Transform Air Force intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance into a set of premier military intelligence organizations with the most respected personnel and the most valued ISR capability.”

“We have made significant progress on that journey,” said Lt. Gen. David A. Deptula, deputy chief of staff for ISR, the so-called A-2 of the Air Force, during an interview in his Pentagon office. However, he added, “There is always more to go.”

For Deptula, the need for the ISR overhaul was a no-brainer.

“We are at a transition point between an era of industrial age … warfare to one in which we are in an information age,” he said. The US military is now operating “in an era of much more rapid assimilation and distribution of information,” yet it is “still dealing with processes and organizations” developed in the industrial age of warfare.

|

A U-2 spyplane lands at an undisclosed air base in Southwest Asia. (USAF photo by MSgt. Scott T. Sturkol) |

Muscle Move

“We need to change our processes and organizations to meet that technological shift,” he said.

Deptula spearheaded the ISR changes since he took over the service’s top ISR job in July 2006. The A-2 office is now the focal point for all Air Force ISR matters, ranging from the oversight of RPA programs to monitoring developments across ISR capability portfolios to ensure “the left hand knows what the right hand is doing,” as Deptula puts it.

He said that the biggest organization “muscle move” was USAF’s bringing in of all ISR units under one house so that they could be treated as an integrated whole and serve users across all domains—such as air, space, and cyberspace—as opposed to stratified entities answering to a single command that specializes in one domain. Such domain-centric ownership only decreased ISR effectiveness, he said.

That new organization is AFISRA, which grew out of the former Air Intelligence Agency that was structured under Air Combat Command. AFISRA is a field operating agency that reports directly to the DCS for ISR.

The agency oversees the 480th ISR Wing, at Langley AFB, Va., the organization that manages the Air Force’s worldwide DCGS activities; the 70th ISR Wing at Ft. Meade, Md., the Air Force’s sole cryptologic wing; the National Air and Space Intelligence Center (NASIC) at Wright-Patterson AFB, Ohio; and the Air Force Technical Applications Center, at Patrick AFB, Fla., responsible for monitoring nuclear treaty compliance and detecting nuclear events.

Deptula said the new structure has “had some huge positive benefits.” For one, it allowed the Air Force to realign the DCGS enterprise, which had been inefficiently divided across several Air Force major commands. It now resides under the administrative control of the 480th ISR Wing, but with clearly defined lines of support from the five core Distributed Ground System (DGS) sites to the component numbered air forces that they support.

The five core sites are at Beale, Langley (DGS-1), Osan AB, South Korea (DGS-3), Ramstein AB, Germany (DGS-4), and JB Pearl Harbor-Hickam, Hawaii (DGS-5). They are supported by six Air National Guard DGS sites that analyze about 60 percent of all the full-motion video coming off Air Force ISR platforms today.

This new setup allows for DCGS to be operated as a regionally focused, but globally controlled, weapon system out of Langley. That means that if one of the core sites is fully engaged supporting some missions, 480th ISR Wing officials are able to task another one of the sites to help out.

“We can swing the weight of the effort wherever we need to,” said Heithold, the AFISRA commander. This setup, he continued, “allows us to apportion where needed rather than to build huge ISR capacities in all of the theaters, which we can’t afford to do.”

For example, when the US military, including Air Force drones, mobilized to support humanitarian relief efforts in Haiti after the devastating earthquake hit there in January, the 480th ISR Wing was able to shift DCGS analysts at Beale who had been supporting US Central Command to the relief mission without any impact to the work being done for CENTCOM, said Col. Daniel R. Johnson, 480th ISR Wing commander, during an interview at his headquarters.

“Our ability to flex that mission from one location to another is just incredible,” he said.

|

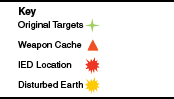

Illustration representing the route that US ground troops took during an August 2009 mission in Afghanistan, supported by SrA. Andres Morales, an intelligence analyst in the DCGS node at Beale AFB, Calif. The soldiers safely traveled the route and, in the process, confiscated three weapons caches and found an improvised explosive device. (480th ISR Wing illustration) |

The DCGS primarily works with U-2 Dragon Lady surveillance-reconnaissance aircraft and MC-12s, along with MQ-1, MQ-9, RQ-4 Global Hawk, and RQ-170 Sentinel RPAs.

“We are the ones who make sense out of what is coming off of the sensors,” said Johnson.

The 480th ISR Wing has also embedded ISR liaison officers with ground forces in Afghanistan as well as Iraq. They “tell us exactly what are the products that the ground troops want,” said Johnson. Army liaison personnel are also now resident at the core DGS sites. A British airman recently became certified for DCGS work, and soon, Australians will be, too.

Last Month’s Game

Along with the DCGS realignment, Deptula said AFISRA’s establishment allowed for the creation of ISR groups that integrate elements of imagery intelligence and signals intelligence drawn from the 480th ISR Wing and 70th ISR Wing to an unprecedented degree in the Department of Defense. This has removed an old seam between the two sources of intelligence, thereby allowing more effective ISR support to the combatant commanders.

“Now we have clear lines of authority and responsibility and function that has dramatically increased the output of ISR to users in each one of the [combatant commands],” he said.

NASIC has also transformed, with a focus on “being operationally relevant,” Col. D. Scott George, center commander, said in an interview in his office. This has been “a big change in mind-set” for NASIC analysts, since their focus in the past was more on long-term analysis, he said.

George has been selected for promotion to brigadier general and is scheduled to receive his star and assume his new post as STRATCOM’s director of intelligence following a June 2 change of command. He follows Jamieson as just the second USAF career intelligence officer to be selected to lead an intelligence directorate for a joint warfighting command in about eight years.

NASIC is the primary producer of foreign air and space intelligence for the nation. Today, it has about 3,000 total staff. George described the center as “the one place in DOD where all sources of intelligence come together.” This includes imagery intelligence, such as geospatial intelligence (Geoint), Sigint, open-source intelligence, foreign material exploitation, and human intelligence, among others.

The center’s analysts are not meant to operate in the same time frames as the airmen in the DCGS. While DCGS analysts are like football referees observing what is happening on the playing field at the moment, NASIC analysts are more like the officials back in the NFL booth.

“We aren’t looking at the game right now, but we look at what happened in yesterday’s game and last week’s game and last month’s game,” George explained. “We are compiling all the information from any of these events to help provide a better understanding of what we think will happen in tomorrow’s game.”

NASIC has also undergone a process of “unitization” to align its internal structure along the lines of the Air Force in groups and squadrons in order to give Air Force officials a better understanding of how to use and leverage the center. But it maintains an overall structure still recognizable to the national intelligence community.

|

An MC-12W ISR aircraft prepares for takeoff at JB Balad, Iraq. The Liberty Project Aircraft went from concept to fielding in just 10 months. (USAF photo by SrA. Brittany Y. Bateman) |

Further, a “distributed mission site” recently stood up at NASIC that is linked into the DCGS enterprise. With it, George said the center is, for the first time, “leveraging broader Geoint into the fight at increased speeds.” NASIC also now regularly dispatches liaison officers to Southwest Asia to help get the word out on how the center can support the warfighter.

Heithold said AFISRA had made the brunt of its organizational changes; now it is making some refinements to apply its finite manpower billets to the areas most in need. For example, it is establishing a human intelligence squadron within the NASIC this summer. There is also “untapped Guard and Reserve capacity” that the agency seeks to access to strengthen the ISR enterprise, he said.

AFISRA is also working to ensure that 24th Air Force, the service’s new cyber operations arm, receives the intelligence support that it needs. To that end, the agency is standing up a new ISR group under the 70th ISR Wing this summer to support 24th Air Force.

“They require signals intelligence,” Heithold said. “We haven’t quite got all of those pieces right yet, but we are stepping through that.”

Despite the successes, many issues lie ahead for the Air Force’s ISR force. Among them, the service is still under strain to fill the thousands of spots needed for airmen to operate and maintain its burgeoning RPA fleet and to process, exploit, and disseminate the information produced by their sensors.

For example, the 480th ISR Wing currently has about 4,100 total personnel, but will grow by nearly 2,200 billets in the next several years. “ISR is a future mission growth area for the Air Force, and we encourage the kids in high school to come join the Air Force and be imagery analysts or signals analysts,” said Johnson.

Like Rain

There has been talk that the Air Force’s ISR enterprise may morph into a major command at some point. Last September, the Air Force held an ISR summit and this idea was mulled, but the decision was made to maintain the current setup and see how developments unfold.

“This is a pretty new organization and it has been working very, very well. That is the key,” said Deptula. However, “I do support the idea of having a majcom for ISR to serve the entire Air Force. I don’t support putting ISR underneath a domain-focused majcom.”

There is also a new DOD push to integrate ISR professionals in the acquisition community so that there is more intelligence input as major new weapon systems are developed. Along those lines, NASIC is “pushing really hard” to get weapons developers to think differently about the design of new systems, said George.

For example, the F-35 Lightning II strike fighter will be a sophisticated platform with state-of-the-art sensors. For the aircraft to be effective, its sensors “have to be smart on what the threats are,” said NASIC spokesman James K. Lunsford.

Whereas in the past, the center’s input came only in the early stages of an acquisition program, it now remains engaged and continues to inject updated threat data as the design of the new weapon system matures.

For Deptula, there is also the issue of how one approaches new aircraft designs. Designations such as “bomber” are outdated, he contends. “Every shooter we build needs to be an effective sensor system,” he said. “And every sensor we build ought to have the capability to achieve some sort of kinetic effect.” Accordingly, the new “bomber” that the Air Force acquires is more accurately deemed an ISR-strike platform.

His office has also been working on a new naming construct to potentially supplant “combat air patrol” as the term used to measure ISR sufficiency. “There is a big difference” between a normal CAP today and one with MQ-9s carrying the new Gorgon Stare wide-area airborne surveillance (WAAS) pods that are expected in the inventory soon. With Gorgon Stare, one Reaper will be able to provide 10 separate video feeds at once, vice just one today. Later versions will be capable of many more simultaneous feeds.

That, in turn, brings up the issue of what is the best way to quickly add more overhead ISR capability, said Deptula. “If you want to get capability out there soonest, the way to do it is by buying more WAAS pods,” he said, noting that this option is also much more affordable, doesn’t take up any more ramp space at the operating bases in theater, and doesn’t require more RPA pilots.

|

Members of the 380th Expeditionary Aircraft Maintenance Squadron prepare an RQ-4 Global Hawk remotely piloted aircraft for a combat mission at a forward base. (USAF photo by MSgt. Scott T. Sturkol) |

There is also the need to start designing RPAs that are survivable in contested airspace. “When we get into environments that are populated by advanced air defense systems,” RPAs “are going to be falling from the sky like rain,” said Deptula.

There are also “huge questions yet to be resolved” facing all of the services regarding RPAs, with no single senior DOD organization having responsibility for dealing with them.

Deptula said they include arriving at an optimal joint concept of operations, airspace deconfliction, and air defense in the face of greater numbers of RPAs flying around, perhaps including enemy remotely piloted assets in large numbers at some point.

“The bottom line is, this is no time for ‘old think,’” he said. “We have got to take some new approaches to the way we move into the future. It is not just an option. Given the increased demand and fewer resources we have available, it is an imperative.”