In the 1960 presidential election campaign, Democratic candidate John F. Kennedy raised the alarm about a “missile gap” in which he said the United States trailed dangerously behind the Soviet Union.

Kennedy’s claims were later revealed to be in error. There indeed was a missile gap, but it was in favor of the United States, which had four or five times as many ICBMs as the Soviets did. The US Polaris submarine-launched ballistic missile was newly operational, whereas the Soviet Union did not yet have any SLBMs.

Kennedy knew this all along. At the direction of President Dwight D. Eisenhower, the Democratic candidates had been briefed by the CIA, Strategic Air Command, and the Joint Chiefs of Staff.

| ||

|

A U-2 flies an ISR mission over the Caribbean. The spyplanes were used to obtain proof that the Soviets were installing nuclear missiles in Cuba. |

The notion of a missile gap also was promoted by Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev, who was often carried away by his own bluster, exaggeration, and boasting. Khrushchev was well aware of the true situation but he fed the impression of superior Soviet strength at every opportunity. He said the USSR was turning out missiles “like sausages” and added, “We have rockets capable of landing in a particular square at a distance of 13,000 kilometers.”

In actuality, Khrushchev was deeply worried about the Soviet disadvantage in long-range missiles, which was about to become the critical factor in both the beginning and the end of what history would call the Cuban Missile Crisis.

“I had the idea of installing missiles with nuclear warheads in Cuba without letting the United States find out they were there until it was too late to do anything about them,” Khrushchev said.

On a trip to Bulgaria in May 1962, Khrushchev took a brief holiday at the Black Sea resort of Varna. As he strolled along the beach, he thought about his problems. The most serious of these was the disparity in strategic military power, but Cuba—the USSR’s first and only ally in the Western Hemisphere—also was on his mind.

The United States had been embarrassed the previous year by the failure of the Bay of Pigs invasion, but US efforts to overthrow Fidel Castro’s regime in Cuba continued. Lately, Castro’s allegiance to Soviet leadership had weakened as he drifted toward the Chinese, who espoused a more aggressive brand of Communism. Khrushchev needed a dramatic demonstration of his commitment to Cuba.

Walking alongside Khrushchev on the beach was Defense Minister Rodion Malinovsky, who pointed toward the opposite shore of the Black Sea, where the Americans were deploying intermediate-range Jupiter missiles in Turkey. “Why then can we not have bases close to America?” Malinovsky asked.

| ||

|

This photo, taken from a U-2 by USAF Maj. Richard Heyser, clearly shows a convoy of Soviet trucks snaking toward San Cristobal, Cuba, on Oct. 14, 1962. This image convinced the CIA that the Soviets were placing nuclear weapons in Cuba. ( |

Indeed, putting missiles in Cuba would address several problems. “In addition to protecting Cuba, our missiles would have equalized what the West likes to call ‘the balance of power,’ ” Khrushchev said. The USSR had plenty of medium- and intermediate-range missiles. From Cuba, they would have the range to strike targets in the United States as easily as ICBMs could from launch sites in the Soviet Union.

The trick was to get it done before the Americans caught on and took preventive measures.

The plan as fleshed out by the Soviet armed forces was to send 24 SS-4 medium-range ballistic missiles and 16 SS-5 intermediate-range missiles to Cuba. From there, the SS-4s could reach as far as SAC headquarters in Omaha and the SS-5s could cover the entire continental United States. The deployment also would include four combat regiments, advanced SA-2 surface-to-air missiles, MiG-21 interceptors, and Il-28 light bombers.

Castro was not enthusiastic about the idea at first but agreed to it as an act of solidarity with the socialist bloc. He also welcomed the opportunity to stand up to the United States.

Marshal Sergei Biryuzov, head of the Soviet rocket forces, visited Cuba prior to the deployments and assured Khrushchev that the missiles could be disguised as coconut palm trees, which had the same straight barrel trunk. “Only the warhead would have to be crowned with a cap of leaves,” said Khrushchev’s son Sergei, a missile engineer in whom the premier confided. “To this day I can’t understand how father believed such primitive reasoning.”

Fundamental to Khrushchev’s decision was his belief that Kennedy was weak and could be bulldozed. He formed this impression on the basis of Kennedy’s fumbling in the Bay of Pigs operation in 1961 and on the Vienna summit that summer, where Khrushchev had pushed Kennedy around at will. Kennedy also vacillated at several points in the Berlin Wall confrontation that fall.

At the end of 1961, Khrushchev told a group of Soviet officials that Kennedy would do anything to prevent nuclear war. “Kennedy doesn’t have a strong background, nor generally speaking, does he have the courage to stand up to a serious challenge,” he said.

| ||

|

A map of the Western Hemisphere shows the range of the nuclear missiles placed in Cuba. (CIA map via The John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum) |

The Kennedys—the President and his brother and closest advisor, Attorney General Robert Kennedy—had not lost interest in Cuba after the Bay of Pigs fiasco. In November 1961, the President authorized Operation Mongoose to foment an uprising in Cuba and overthrow Castro. The project was overseen by Bobby Kennedy with the flamboyant Edward G. Lansdale, the Administration’s favorite insurgency specialist, as operations chief.

Mongoose endorsed sabotage, psychological warfare, propaganda, infiltration by guerillas, disinformation, and much more. Not revealed until much later were half-baked schemes to assassinate Castro with exploding cigars or to use depilatories to make his hair and beard fall out.

Cuban-Soviet fears of an invasion were not totally unfounded. In early 1962, as part of Mongoose, the US military developed contingency operation plans for the invasion and occupation of Cuba. A wargame in August 1962 featured a mock assault on the Puerto Rican island of Vieques and the simulated overthrow of a leader named “Ortsac,” or Castro spelled backward.

The Big Deployment

Never before in its history had the Soviet Union undertaken such a massive sealift. Ships loaded at a dozen Baltic and Black Sea ports and began moving out in July 1962. Until the ship captains opened their sealed orders at sea, they did not know their destination was Cuba.

US aerial surveillance noticed the ships under way and reported that they were riding high in the water, indicative of military cargo such as missiles, which are large in relation to their weight.

Khrushchev continued his bluster. “You don’t have to worry,” he told Cuba’s Che Guevara in July. “There will be no big reaction from the US side. And if there is a problem, we will send the Baltic Fleet.”

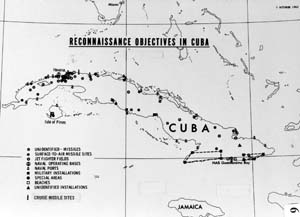

| ||

|

A map used by USAF and the government during the Cuban Missile Crisis shows the locations of valuable reconnaissance targets. (USAF image) |

By late July, two Soviet ships a day were arriving in Cuba. US intelligence spotted the MiG-21s and Il-28s and watched the buildup of troops. In August, Central Intelligence Agency U-2 spyplanes overflying Cuba found SA-2 SAM sites at eight locations. The White House judged the SAMs to be purely defensive and not a threat.

Anatoly Dobrynin, the Soviet ambassador to the United States, was not told about the missile deployment. On Sept. 4, he relayed a message from Khrushchev assuring Kennedy that no offensive weapons would be placed in Cuba. This was one of the several lies by Khrushchev during the Cuban Missile Crisis. In his opinion, US duplicity during the U-2 overflights of the Soviet Union in the 1950s entitled him to use whatever deceptions he wished.

Khrushchev planned to announce the presence of the missiles in a speech at the United Nations in November, when his entire force was in place. At the end of September, he told an aide, “Soon, hell will break loose.”

A U-2 made a regular run over Cuba on Sept. 5, but owing to events halfway around the world, that was the last overflight for five critical weeks.

On Aug. 30, a Strategic Air Command U-2 on a mission unrelated to Cuba overflew Sakhalin island in the Far East by mistake. The Soviets protested and the US apologized. On Sept. 9, another U-2, flown by a pilot of the Taiwanese Air Force, was lost, probably to a SAM, on a mission over western China.

Tass, the Soviet news agency, published a warning against interference with the ships bound for Cuba, which in any case carried only farm machinery and industrial equipment, along with “agronomists, machine operators, tractor drivers, and livestock experts” sent to help the Cubans.

Secretary of State Dean Rusk and National Security Advisor McGeorge Bundy stirred up enough concern about the political consequences if a U-2 were to be shot down over Cuba that there were no overflights from Sept. 5 to Oct. 14.

| ||

|

A map used by USAF and the government during the Cuban Missile Crisis shows Cuba’s naval bases. (USAF image) |

Unseen by the United States, the Soviet cargo ship Poltava docked at Mariel Sept. 15, carrying the first of the SS-4s. On Oct. 4, Indigirka arrived at Mariel with 90 nuclear warheads to arm the missiles, bombers, and the battlefield nuclear weapons code-named Frog and Salish by NATO.

During this interval, the Cuba overflight mission was reassigned—over CIA objections—to Air Force U-2 pilots. Various reasons were given for the change, among them the rising prospect of armed conflict.

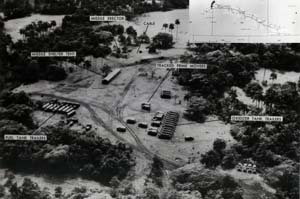

When overflights resumed Oct. 14, Air Force Maj. Richard S. Heyser flew the first mission. He approached Cuba from the south an hour after sunrise, crossed the Isle of Pines, and turned on his cameras at 7:41 a.m. He passed over San Cristobal west of Havana, exited Cuban airspace 12 minutes after he entered it, and headed for McCoy AFB, Fla., where a courier airplane was waiting. Heyser’s film was soon in the hands of the CIA’s photo interpretation center in Washington, D.C., which on Oct. 15 confirmed components of SS-4 missile batteries at San Cristobal.

Showdown

President Kennedy was notified at 8:45 a.m. Oct. 16, marking the beginning of the famous “Thirteen Days” of the Cuban Missile Crisis, also remembered as “High Noon of the Cold War”—when the danger of nuclear war reached its peak.

| ||

|

Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev at a meeting of the United Nations in 1960. Despite his bombast, he was deeply worried about the “missile gap”—which favored the US. ( |

In a White House meeting the afternoon of Oct. 18, Soviet Foreign Minister Andrei Gromyko—who, unlike Dobrynin, did know the details of the missile deployment—assured Kennedy that no offensive weapons were being delivered to Cuba. Kennedy knew that Gromyko was lying but did not say so.

U-2 flights increased and the CIA reported on Oct. 20 that four SS-4 sites were in place with 16 operational launchers, and that two SS-5 sites and at least one nuclear warhead storage bunker were under construction.

Recalling it years later when he wrote his memoirs, Khrushchev still had not shed his braggadocio. “We hadn’t had time to deliver all our shipments to Cuba, but we had installed enough missiles already to destroy New York, Chicago, and the other huge industrial cities, not to mention the little village of Washington,” he said. However, Khrushchev had seriously miscalculated the American response and Kennedy’s determination.

The cockpit from which Kennedy would work the crisis was “ExComm,” the executive committee of the National Security Council. Rusk regarded it as a device to give Bobby Kennedy a prominent role and marginalize the State Department. ExComm struggled with the missile crisis for a week before the public was informed.

A nuclear missile threat 90 miles from Florida could not be tolerated. The Joint Chiefs of Staff advised an air strike, but when told it might take several hundred bombing sorties to get 90 percent of the missiles, Kennedy decided instead on a “quarantine,” a euphemism avoiding the term “blockade,” which would be an act of war. Strategic Air Command went on airborne alert.

In an electrifying speech to the nation Oct. 22, Kennedy said there was “unmistakable evidence” of Soviet missiles and bombers in Cuba. He announced the quarantine and said the US would “regard any nuclear missile launched from Cuba against any nation in the Western Hemisphere as an attack by the Soviet Union on the United States, requiring a full retaliatory response against the Soviet Union.”

For the first time in history, SAC advanced its alert posture to DEFCON 2, one step short of nuclear war, and North American Air Defense Command sent interceptors and anti-aircraft batteries to the southeastern United States.

“We moved into Florida,” said Gen. David A. Burchinal, who was director of plans on the Air Staff at the time. “I thought it would sink in terms of tactical air forces that we moved in to Florida—airplanes, bombs, and rockets.” Air Force and Navy fighters began low-level reconnaissance of Cuba to supplement the high-altitude surveillance by the U-2s.

On Oct. 22, SAC activated its first 10 Minutemen ICBMs and placed them on alert.

Khrushchev had two regiments of SS-4s operational but he understood right away that his plan had failed. “We missed our chance,” he said later. He had assumed that Kennedy would back down rather than risk war over the missiles in Cuba. “It turned out that we had no carefully thought-out plan in case our missiles were discovered prematurely,” Sergei Khrushchev said. “Now we would have to improvise.”

Bait and Switch

For a while on Friday evening, Oct. 26, it seemed that the crisis had broken when the State Department received a long, rambling letter from Khrushchev to Kennedy, hinting at a possible basis for settlement.

| ||

|

The shadow of a US RF-101 aircraft passes a Soviet cargo ship during a November reconnaissance mission over Cuba. The vessel was loaded with missile transporters. (USAF photo) |

“We, for our part, will declare that our ships bound for Cuba are not carrying any armaments,” Khrushchev proposed. “You will declare that the United States will not invade Cuba with its troops and will not support any other forces which might intend to invade Cuba. Then the necessity for our military specialists in Cuba will be obviated.”

The letter contained more lies. “I assure you that the vessels which are now headed for Cuba are carrying the most innocuous peaceful cargos,” Khrushchev said. “The ships bound for Cuba are carrying no armaments at all. The armaments needed for the defense of Cuba are already there.” Among the ships en route to Cuba was Poltava with 24 SS-5 ballistic missiles aboard.

Before Kennedy could respond to the proposal, Radio Moscow broadcast a new message from Khrushchev at 9 a.m. Saturday changing the offer. The Soviets now said they would remove their missiles from Cuba only if the United States withdrew its Jupiters from Turkey.

The Jupiters were essentially obsolete and not regarded as all that important. Had they been included in Khrushchev’s original proposal, Kennedy might have agreed. As it was, Khrushchev appeared to be engaging in bait-and-switch tactics, which aroused US suspicions.

Saturday would be the longest day of the crisis, when three separate incidents propelled the United States and Cuba to their closest brush with nuclear war.

That morning, Air Force U-2 pilot Maj. Rudolf Anderson Jr. took off from McCoy, crossed the Cuban coastline at 9:15, and was soon picked up by the SAM site at Banes in eastern Cuba. Castro—who had no control over the Soviet weapons—had been clamoring for the U-2s to be shot down but Moscow would not give permission.

An enlarged, low-level photo of the San Cristobal site reveals in detail the nuclear nature of the Soviet presence on Cuba. Note the missile erector under a tarp at top. Inset: The arrow points to San Cristobal. (USAF photos)

On Oct. 27, however, the Soviet commander, Gen. Issa Pliyev, could not be found and his deputy gave the order to fire, in violation of orders. The batteries launched three SAMs, two of which hit the U-2 and knocked it out of the sky at 10:19 a.m. Anderson was killed. The Air Force wanted to launch an F-100 air strike on Banes, but Kennedy would not authorize it.

Khrushchev denied responsibility but Sergei Khrushchev later said, “Father was inwardly pleased that another U-2, which had inflicted such humiliation on our country, had been downed by a Soviet missile.”

Meanwhile, another Air Force U-2 had gone missing in the far north. It had taken off from Alaska on a mission to collect air samples at high altitude to monitor Soviet missile testing. The pilot, his navigation confused by the northern lights, drifted into Soviet airspace around noon, Washington time.

Six Soviet fighters took off to intercept the U-2, and American F-102s, armed with tactical nuclear rockets because DEFCON 2 was in effect, scrambled to protect the aircraft, which managed to return to US airspace before a confrontation occurred.

Tensions were running high at 5:59 p.m. when US destroyers, enforcing the quarantine, dropped practice depth charges about the size of hand grenades in an attempt to force a Soviet submarine to surface. Unknown to the US Navy, the submarine was armed with a nuclear torpedo and had orders to use it if the submarine was hulled by depth charges or surface fire. The submarine had to surface for air at 9:52 p.m. The captain was angry but made a radio check with Moscow and was told to hold his fire.

Three incidents were thus defused, but that evening, Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara wondered if he would “live to see another Saturday night.”

Khrushchev Blinks

Around 8 p.m. Saturday, ExComm hit upon the stratagem that brought the crisis to a close. Kennedy would respond to and accept Khrushchev’s offer of Friday night and ignore the Saturday morning addition about the Jupiters.

Bobby Kennedy, who had held several back-channel sessions with the Soviets during the crisis, met with Dobrynin and told him that unless Khrushchev made a commitment by the next day to dismantle the missiles, the United States would begin military action against Cuba. If the Soviets removed the missiles, the Jupiters would be taken out of Turkey, although there would be no public announcement of that.

“We could see that we had to reorient our position swiftly,” Khrushchev said. He knew that the USSR was years away from achieving strategic parity. At the time, according to McNamara, the US had 5,100 nuclear weapons it could deliver on the Soviet Union compared to 300 the Soviets could deliver on the United States. Khrushchev feared that a nuclear exchange would wipe his country off the face of the map, whereas the US would sustain millions of casualties but survive.

At 9 a.m. Sunday Washington time, Khrushchev broadcast a message on Radio Moscow saying that he had ordered “the dismantling of the weapons you describe as ‘offensive’ and their crating and return to the Soviet Union.” The missile crisis was effectively over. “Eyeball to eyeball, they blinked first,” Rusk said.

Castro was not informed in advance. “Father decided to present Havana with a fait accompli,” said Sergei Khrushchev. In a rage, Castro peppered Khrushchev with “son of a bitch, … bastard, … no cojones,” and other epithets.

Reconnaissance on Nov. 1 found the missile sites bulldozed and the missiles removed. By December, all of the strategic missiles and the Il-28 bombers were gone. The Jupiters were quietly pulled out of Turkey, with Polaris submarines deployed to take over their function.

| ||

|

President John Kennedy (l) and Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara in a National Security Council Excomm meeting. (National Archives photo) |

In January 1963, Rusk testified at a closed hearing of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee that the promise of on-site inspections in Cuba had not been fulfilled, and that the United States did not consider its noninvasion pledge binding “if Castro were to do the kind of thing which would from our point of view justify invasion.”

By personal direction of the President, Rudolf Anderson was posthumously awarded the Air Force Cross for heroism. This was the first time this new decoration, second only to the Medal of Honor, had ever been presented.

According to postcrisis intelligence analysis, there had been 40,000 Soviet troops in Cuba, many more than the US had estimated. Five of the SS-4 sites had been operational, with 33 missile launchers. The Soviets had about 20 nuclear warheads in country although none of them had been mounted on the missiles. The SS-5 missiles, aboard the cargo ship when the quarantine began, never reached Cuba.

Kennedy had demonstrated courage during the crisis, stood firm, and played his hand well. He was careful not to boast in public, but others—including his admirers in the news media—were more than ready to heap credit on him. Both Kennedy and Khrushchev contributed to the peaceful outcome by their exercise of restraint.

Immediately after the crisis, the Soviets publicly depicted it as a triumph that prevented an invasion of Cuba. Pravda said that Soviet “calm and wisdom” had saved the world from a “nuclear catastrophe.”

The Russians didn’t really believe it, and any benefit to Cuba was vastly outweighed by the spectacle of the Soviets withdrawing their missiles and forces in a losing confrontation with the United States.

In October 1964, Khrushchev was removed from power and forced into retirement. There were various reasons for his ouster, not the least of them being the humiliation suffered by the Soviet Union in the Cuban Missile Crisis.

John T. Correll was editor in chief of Air Force Magazine for 18 years and is now a contributor. His most recent article, “The Muddled Legend of Yalta,” appeared in the September issue.