America’s nuclear deterrent is considered foundational to the nation’s defense, and the 1970’s-vintage Minuteman III fleet of 450 missiles, spread across silos in five states and three sprawling bases, is its cornerstone.

That foundation, however, is crumbling. Defense officials warn that the Minuteman is long overdue for replacement, especially since Russia—even as its conventional forces saw ups and down over the last 25 years—has never stopped modernizing its strategic forces. China’s strategic forces have advanced tremendously in just the last decade. North Korea’s missiles may soon be a credible threat.

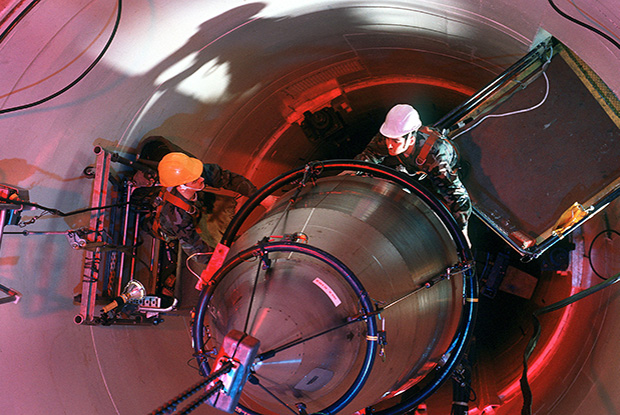

The Minuteman infrastructure has not substantially changed since the Cold War. Missile crews operate equipment with such antiquated technology that some of it requires eight-inch floppy disks. Communications and control systems linking National Command Authorities and missileers to the Minuteman IIIs are every bit as important as the missiles themselves—Air Force leaders have described this infrastructure as the “fourth leg” of the nuclear triad—and it’s judged to be obsolete.

Modernizing the Ground-Based Strategic Deterrent will be so expensive that both supporters and critics say it may prove unaffordable.

Still, “having a safe, secure, and reliable nuclear deterrent is a bedrock priority,” Defense Secretary Ashton B. Carter told lawmakers in March. “And we give it the highest priority.”

In addition to the missiles themselves, USAF is planning to replace nearly every aspect of the ICBM enterprise, including alert centers, command and control, and communications equipment. The scope of the program is unprecedented.

“One new approach which has not been used before … is to look at the GBSD as a total capability,” Air Force Secretary Deborah Lee James told lawmakers in February budget testimony.

“Don’t just look at the ICBM missile and then separately look at the missile alert facility and then separately … at some other component, but … look at the entirety of it, because it needs all of those pieces in order to be a strategic deterrent,” she said.

The GBSD program has begun in earnest, with $113 million requested for Fiscal 2017 research and development. The Air Force expects to spend $62.3 billion in then-year dollars over 30 years on the program, to acquire nearly 650 new missiles. That figure includes units for both deployment and test, according to a March Congressional Research Service report.

The Modernization Bill

In May, Pentagon acquisition, technology, and logistics chief Frank Kendall said the bill to modernize the whole nuclear triad—including the B-21 bomber, new ballistic missile submarines, and a new standoff cruise missile—will cost $12 billion to $15 billion a year.

The Air Force’s need to rebuild the ground-based leg of the triad overlaps with a heady program of other modernization. New fighters, bombers, tankers—all of them described by USAF Chief of Staff Gen. Mark A. Welsh III as “existential” to the service—join new trainer jets, radar sensor aircraft, a new rescue helicopter, and other big-ticket programs on USAF’s shopping list. Collectively, it’s become known as the Air Force’s modernization “bow wave.” Few believe there will be enough money to do it all.

The Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments, in a 2015 report, questioned whether continued investment in the nuclear force is affordable. The projected costs, adjusted for inflation, will grow by 56 percent and peak around Fiscal 2027.

“The Pentagon’s spending plans exceed its available resources, a situation that is likely to persist for the next five years while the budget caps in the [Budget Control Act] remain in effect,” the report states. “That means that any aspect of the defense budget … could be described as ‘unaffordable.’ This description appears to be particularly ill fitting for nuclear forces, however.”

Jamie M. Morin, the Pentagon’s director of cost assessment and program evaluation, said during a March speech at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, that unless the Pentagon can divest one leg of the triad, nuclear modernization isn’t affordable given expected budget levels. A projected surge in needed funding comes in Fiscal 2021 as the Navy’s Ohio-class submarine hits its target procurement date, while the B-21 bomber and GBSD programs enter advanced development and production.

The investment required to update the nuclear enterprise is so daunting that other experts have called for scrapping the ICBM leg altogether. William J. Perry, Defense Secretary from 1994 to 1997, said during a recent meeting with reporters in Washington, D.C., that getting rid of ICBMs is “something that I don’t think [is] going to happen, but I think it should happen.” The missiles are an “attractive nuisance” because while they’re meant to serve as a credible deterrent, there’s the danger of a false alarm that, “having lived through it before, … seems very real to me,” Perry said.

“They do have that very beneficial effect” of deterrence, Perry said. “But the question is, how much do you need for deterrence? Do you need more than 2,000 warheads and submarine forces? Do you need more than however many for the bomber forces? My answer to that has always been no. So why … in the Cold War did we build tens of thousands of them? It never had to do with simply maintaining deterrence. It had to do with keeping up with the Joneses.”

Despite the sticker shock, though, the question isn’t whether the country can afford to modernize the nuclear triad, but rather, “can we afford not to?” says Adm. Cecil D. Haney, commander of US Strategic Command.

The ICBM force, as part of the triad, is “foundational to our nation’s defense,” Haney said during a March AFA event in Silverdale, Wash. China and Russia are significantly investing in their nuclear capability—both the missiles and attendant infrastructure, he pointed out.

Going Underground

In response, the US may not necessarily have to tit-for-tat match the new capabilities, but must be mindful of the threat and maintain the triad “so there’s no doubt the President has options if so desired.”

“The world’s gone mobile and gone underground,” Haney warned. Modernization is a must to maintain “strategic stability,” he said.

In 2015, Congress acted to protect at least some of the nuclear modernization effort by creating the National Sea-based Deterrence Fund. This account—funded separately from the Navy’s other procurement—protects investment in the Ohio-class replacement, a program with an estimated $139 billion pricetag.

The move prompted the Air Force to push for a similar fenced account for its nuclear modernization programs, including the GBSD and B-21 bomber. At an AFA event in February, James said there are discussions about such a fund, and that USAF is “making progress.” A few weeks later, she said at a Pentagon press conference that if there is to be a fund for nuclear modernization, it would be “appropriate” for it to cover all three legs of the triad and not just the sea-based one.

“The key question, though, is where will the money come from, and this is where we’re simply going to have to have a national debate,” James said. “It’s probably not going to be settled this year, but it needs to be settled in the next few years. Are we or are we not going to modernize these forces? And if we are, we must have the appropriate resources to do it.”

Lt. Gen. Stephen W. “Seve” Wilson, Haney’s second in command at STRATCOM, relates the strategic situation to poker. With the large-scale ICBM force dispersed across five Great Plains states, the US has an advantage over countries with a smaller fleet.

“I think having a very affordable deterrent capability, like today’s ground-based deterrent … makes great sense to our country,” Wilson said at a May 6 AFA Mitchell Institute event on Capitol Hill. “It means an adversary has to go all-in with a large number of weapons.”

An adversary would have to focus on 450 missile targets plus their 45 affiliated launch-control sites, all located across a huge swath of territory, simply to attack the ground-based leg of the triad. If there were no silo-based ICBMs, a potential adversary could launch an attack much more focused on the small number of bomber bases and submarine bases, making it far more likely he could destroy the majority of the US nuclear retaliation capability.

Chinese officials have said North Korea has 10 ICBMs, a number that potentially could destroy the intellectual capability at national laboratories, along with the production, delivery, and storage of nuclear bombs.

For nations with small nuclear arsenals, however, attacking the ground-based deterrent represents a poor return on investment. Nearly all US ICBMs now carry a single warhead, but a potential attacker could not count on a one-for-one kill ratio. An enemy could well need to send 900 nuclear missiles if the goal is to take out 450 Minuteman IIIs.

In the Fiscal 2017 budget cycle, the Pentagon is pressing ahead with the ground-based strategic deterrent. Kendall told lawmakers on April 20 the program is on track, and “it’s very important that … we do it in a timely way. So we’re not slowing the program down at all.”

The department planned three steps in June: to ask industry for risk-reduction ideas, hold the “Milestone A” program go-ahead meeting, and develop an initial cost estimate, Kendall said.

“It’s going to be an expensive system, by any metric, so that’s going to be one of the things we’re looking at very carefully,” Kendall said. “It is a system of systems; it’s not just the missile. It’s also the infrastructure, including the command and controls. We have to look at all of that.”

The first priority, “due to system age-out,” needs to be the missile itself, said Gen. Robin Rand, the commander of Air Force Global Strike Command. But the entire enterprise needs to be a priority.

“Command and control (C2) and infrastructure recapitalization is necessary to continue safe, secure, and effective operations,” Rand told Congress in March. “It is no small task to upgrade the command and control systems along with the underlying infrastructure that supports the weapon system.”

For example, Rand noted that the largest missile field in the Air Force, Malmstrom AFB, Mont., operates hardened infrastructure across 14,000 square miles, an area larger than Maryland. The base uses buried copper

wire and equipment from the 1960s.

Seeking Commonality

“GBSD cannot be viewed as just another life extension” to Minuteman III, Rand said. “It is time to field a replacement ground-based capability that will continue to assure our allies and deter potential adversaries well into the future.”

One of the ways to get the cost of nuclear modernization under control will be commonality. The Air Force and Navy, and other agencies, are looking to work together to better modernize their weapons systems and reduce costs.

“The Navy and the Air Force are both addressing challenges in sustaining aging strategic weapon systems,” said Vice Adm. Terry J. Benedict, the Navy’s director of strategic systems programs, during a March congressional hearing. Nine teams within the Pentagon have found “numerous opportunities where commonality has the potential to reduce not only cost, but also risk” for both the GBSD and the Navy’s Trident II D5 next generation submarine-launched ballistic missile.

Benedict, at a different event, expanded on another common effort with the potential to save hundreds of millions of dollars. If the Navy and Air Force jointly develop a fusing firing circuit that could work for either ICBMs and SLBMs, this approach alone could save about $600 million in unique development costs. The joint fuse, with a target initial operational capability of 2019, is designed for both the Minuteman III and Trident, with projected use in future weapons systems. It’s “a perfect example of services doing something we’ve never done before,” he said.

Rand said the Air Force is looking across the board for any similar overlapping requirements to reduce “design, development, manufacturing, logistics support, production, and testing costs,” though different systems will have different requirements and missions. The service is also working with the National Nuclear Security Agency to develop a life extension program for the W78 warhead used on the Minuteman III and projected to be used in GBSD, Rand told Congress.

While the road ahead for GBSD is long, replacing it is necessary. If the legacy system is simply allowed to “decay,” Haney said, “we’d have to deal with the ramifications,” and “that’s not a good position to be in.”

Rand sounded the alarm to lawmakers. While Global Strike Command airmen continue to maintain and secure the aged system so that it’s the most responsive leg of the triad, it cannot remain that way for too much longer. In 20 years, Rand pointed out, Minuteman may not be able to reach its intended targets because they’ll be well-defended with advanced defensive technologies.

“We need to continue to fund … the GBSD” and ensure that it’s “fully operational … no later than 2030,” Rand said. “My large reason for that is the Minuteman III, with each year, becomes more and more obsolete, and I am concerned that if we don’t replace it, that the enemy gets a vote and we will not be able to provide the capabilities that are needed.”