A pilot and crew chief ready an F-35 for taxi at Luke AFB, Ariz. Photo A1C Jacob Wongwai

The F-35 is expected to complete initial operational test and evaluation late this year, certifying the Block 3F version is fully combat-ready. By that time, work will be well underway for dozens of planned upgrades, collectively known as Block 4.

Block 4 comprises some 53 improvements to counter both air- and ground-based threats emerging from China and Russia. None of these upgrades will change the aircraft’s outer appearance, or “mold line.” Instead, they are primarily new or enhanced features executed in software, which will be rolled out in stages, with updates every April and October starting in 2019 and continuing through at least 2024.

“Instead of doing two-year deliveries … we decided to go to a more continuous capability framework,” said Vice Adm. Mathias W. Winter, F-35 Program Executive Officer, in a December interview.

Now that Block 3F has been “verified and validated,” the Lightning II is a “mature” system, Winter said, and ready to accept “modernization, enhancement, and improvements.” Exactly how many early production F-35s will be upgraded to the 3F configuration may be revealed in the 2020 budget submission to Congress.

An F-35 fires an AIM-9X missile during a test over the Gulf of Mexico in June 2018 near Eglin AFB, Fla. Block 4 upgrades will enable the Lightning II to fire up to seven additional weapons. Photo: SSgt. Brandi Hansen

Most existing F-35s are getting the Technology Refresh 3 package. Known as TR3, Winter said it includes “updated cockpit displays, updated memory system capacity, and updated core processing and computer power.”

Together, these “ensure that we have growth [capacity] well into the 2030 time frame.”

In fact, TR3 makes the Block 4 improvements possible, Winter said.

“Think of TR3 [as] your brand-new … laptop that has a new cool display with better graphics. It has a new processor inside so it can go faster, and it’s got terabytes of storage and memory system in there.” The Block 4 upgrades are like “the programs; the applications and outcomes that fill your computer.”

Handled at the squadron level, TR3 upgrades can be completed “in a couple of days,” Winter said. That’s in contrast to TR2 modifications that require depot-level installation of structural and component improvements.

The Block 4 upgrades will be “80 percent” software, Winter said, and delivered more rapidly than in the past.

Block 3F “allowed us to … do software faster,” according to Winter. “We can [now] go to a more agile, relevant, and flexible code-verify-test-deliver cadence, based on the warfighter’s direction to us [and] based on what capabilities they need, [and] when, to pace the threat. So, that’s the philosophy.”

Winter calls this Continuous Capability Development and Delivery, or C2D2.

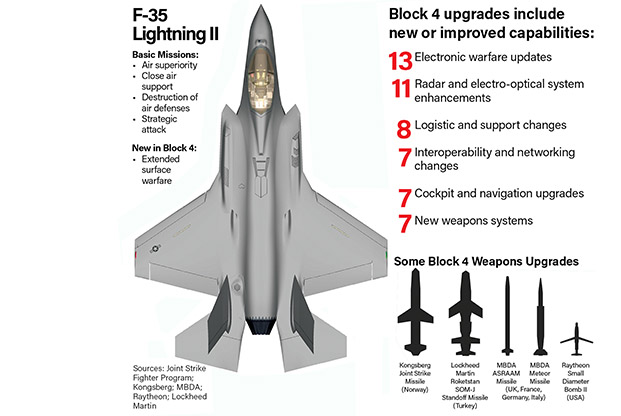

F-35 Block 4 graphic. Staff graphic

RISK VS. THREAT

The Government Accountability Office recommended last June that Block 4 be delayed until initial operational testing was complete, but Winter certified that the rapid advance of threat systems posed an urgent risk, and the Pentagon proceeded with a Block 4 contract award in November.

Block 4 includes 53 new capabilities “mapped … to six-month delivery cycles over the next six years, to 2024,” Winter said.

Updating every six months instead of every two years marks a cultural shift from “the traditional waterfall acquisition to an agile, rapid capability/continuous delivery” model, Winter noted. The new model is more akin to commercial product cycles, where rapid, iterative software releases are now the norm.

Indeed, the last Block 3F software was delivered in December and the first Block 4 update is planned for April 2019.

Combat operators, rather than program managers, will decide how to prioritize the updates, Winter said. If the combat operator wants to “wait, for whatever operational reason, we have the flexibility to be able to do that.”

The specific content of the Block 4 upgrade remains closely held, but breaks down broadly into six categories:

- Integration of seven new weapons, including the Small Diameter Bomb II, British weapons such as the ASRAAM and Meteor air-to-air missiles; Turkey’s Standoff Missile and Norway’s Joint Strike Missile;

- Eight logistics and support changes;

- 13 electronic warfare updates;

- Seven interoperability and networking changes;

- Seven cockpit and navigation upgrades; and

- 11 radar and electro-optical system enhancements.

In addition to those improvements, which will be common to all variants, some updates will answer unique service requirements. For example, Winter mentioned, only the Navy wants its F-35Cs to be able to launch the Joint Standoff Weapon (JSOW) C1 version.

A1C Eric Ruiz-Garcia inspects a Lightning II at Luke AFB, Ariz., in December 2017. Photo: A1C Caleb Worpel

The F-35 has four basic missions: air superiority, or offensive and defensive counterair; suppression or destruction of enemy air defenses (known as SEAD and DEAD); close air support; and strategic attack against high-value strategic and mobile targets.

“The Block 3F can service all four of those,” said Winter. Block 4 “brings on advanced capabilities and enhancements” to counter adversaries as their “capabilities increase against those mission sets.”

Block 4 also adds a fifth basic mission, Winter said: “extended surface warfare.” Upgrades will enhance radar “for maritime surveillance, identification and targeting,” he explained, “because ‘maritime surface’ and ‘land surface’ are two different problems.” Search patterns on the open ocean will be improved, as will “being able to sense the order of battle in the maritime world.”

Although the F-35 can carry the new Long-Range Anti-Ship Missile, or LRASM, externally, Winter said the principal new anti-ship missiles coming in Block 4 are the JSOW C1 for the Navy and the Norwegian JSM. The program has “not been asked” about whether the stealthy LRASM can fit inside the F-35’s weapon bays, he said, nor has the Navy asked to integrate the SLAM-ER (Standoff Land Attack Missile-Extended Range) version of the Harpoon anti-ship missile.

The Block 4 updates identified thus far have a completion point in the mid-2020s. A program official said “there will certainly be other Block updates” to follow. If current production schedules hold, the F-35 will remain in production through at least 2040. A “Block 5” will “probably kick in around 2028-2030,” one Pentagon official suggested, and feature “what we think of today as really ‘out there’ stuff, like lasers.”

Capt. Dayna Grant briefs then-Deputy Secretary of Defense Patrick Shanahan at Hill AFB, Utah. Hill is host to three F-35 fighter squadrons. Photo: Todd Cromar/USAF

‘TECHNICALLY FEASIBLE’

The “tagline” for Block 4 is “‘technically feasible while operationally relevant,’” Winter said. That term is essential because, “we don’t want to overcommit. It’s got to be technically feasible.”

Besides improvements to the aircraft themselves, Block 4 updates must also be applied simultaneously to ALIS (Autonomic Logistics Information System), the Mission Data Files and training systems, such as simulators.

ALIS maintains an automatic, aircraft-specific logbook of maintenance actions, parts consumption, and noteworthy events (such as overstressing a landing gear door or an accident affecting stealth surfaces), then maps these data points across the entire fleet. The system can track trends regarding the actual use and consumption of parts and maintenance man-hours, and thus anticipate future demand.

Mission Data Files have been one of the most laborious projects attending the F-35. A software center at Eglin AFB, Fla., staffed by a small army of computer coders, constantly updates the threats F-35s could encounter in specific regions, and these files are downloaded into the aircraft before operational missions.

The level of detail in the MDFs is extremely fine-grained and includes every fighter, radar, surface-to-air missile battery, airborne sensor aircraft, and other knowable threat. The Israeli Air Force Chief of Staff told an industry source last year that, waiting to take off in the F-35, he already had a “full picture of the entire Middle East” on his displays, including everything airborne and all potential threats.

The MDFs have to be constantly validated and verified to account for even small changes in adversaries’ order of battle.

“The certification/validation philosophy right now is 100 percent,” Winter said. However, it still takes eight months to compile an MDF “because we’re using engineering/manufacturing tool suites that were used to just determine how to do this.”

Winter said the program is set to migrate by April 2019 to new tools that will speed up the process.

Air Force leaders have allowed that they’ve been going slow in buying F-35s.

They prefer to wait for the Block 4 version to start coming off the production line, with all the bells and whistles they want for the bulk of the force. Doing so would reduce the cost of upgrading the fleet.

In order to get there, though, the F-35 must survive as a program.

F-35s refuel from a KC-135 over the Utah Test and Training Range during a combat power exercise in November 2018. Photo: SSgt. Andrew Lee

Undersecretary of the Air Force Matthew P. Donovan said in January that F-35 sustainment costs remain too high.

“F-35 sustainment costs are going to have to come down,” according to Donovan. Compared to 4th-generation fighters such as the F-15, he acknowledged, there is a “tax for LO,” or low observability. However, to be affordable in large numbers, F-35 sustainment costs “have got to be comparable” to those of the aircraft—the F-16, A-10, and F-117—it replaces.

The Air Force has a goal to reduce F-35 sustainment costs by 38 percent, and Donovan said “we are trying to pull that to the left” and accomplish it sooner than predicted.

Last October, then-Defense Secretary Jim Mattis directed the Air Force to increase mission capable rates for the F-22, F-16, and F-35 to at least 80 percent. At the time, the F-35 rate was 54 percent overall, but for 3F aircraft recently off the production line, the rate was better than 80 percent.

Winter agreed that spare parts are the “long pole in the tent” for getting the F-35 fleet up to the 80 percent standard.

“We have initiatives underway to increase spare parts production,” he said, including accelerating the rate at which parts can be repaired by the F-35 depot at Hill AFB, Utah. This will allow industry to concentrate on making more new parts, rather than fixing older ones, he said.

The Air Force has until Sept. 30 to achieve the 80 percent mission capable rate, assuming the order stands under Acting Defense Secretary Patrick M. Shanahan or his successor.

Winter confessed that “supply chain performance” is his greatest concern with regard to readiness, and he also recognizes that sustainment costs are key to keeping the F-35 viable.

“We are getting after that supply chain performance and their ability to meet [our] capacity demands, he said. “So, that’s working.”